I see that Elias has jumped on the study making the rounds that the net worth of America’s wealthiest family, the Walton’s, is greater than the combined net worth of the bottom 30% of Americans combined. I must admit that upon first glance, I was just about equally shocked by this statistic. It certainly seemed that it was quite proper to tout the study as a particularly outrageous example of the severity of income inequality in this country.

But then I looked at the study a bit more closely. It turns out that the study really may be indicative of a severe problem in this country. But the statistic most being cited about the Waltons’ wealth in fact turns out to say extraordinarily little about inequality. Instead, it mostly stands for the proposition that in 2007, just before the housing market crash, around 18% of Americans had more liabilities than assets, and that the next 12% had a net worth just large enough to cover the negative net worth of that 18%. Believe it or not, had the report used the estimates on wealth in 2009, the percentage of Americans with a lower combined net worth than the Waltons would be even more sensational sounding – probably close to 40% – thanks to the devastating effects of the housing crash on net worth.

The study – the full version of which seems to be here – is based on a combination of data from the triennial Survey on Consumer Finances and, for calculation of the Waltons’ wealth, from Forbes magazine’s estimates. As you will see, the Forbes estimates of the Waltons’ wealth are basically irrelevant. Instead, what is important is how the wealth of the rest of us is calculated. “Wealth” is susceptible to any number of different meanings and manners of calculation, many of which are laden with all sorts of normative values, but for purposes of this study, it seems that “wealth” was quite reasonably defined as “net worth,” i.e., current asset values minus current liabilities. Income and expected future income are essentially left out of the equation entirely.

It is entirely reasonable to rely upon this definition of “wealth,” as it is an accepted definition that is mostly devoid of normative valuation problems.

Unfortunately, by defining “wealth” as “net worth,” it is very difficult for any resulting comparison to tell us much of meaning about inequality. This is because of simple math: if a sizable number of people have negative net worth because of student loans, mortgage payments, or car payments, then it will take a sizable number of people with small positive net worth to make the combined total reach a positive number.

So when we say that the Waltons have more wealth than any given percentage of Americans combined, without knowing the specific amount of the Waltons’ combined wealth or the specific amount of wealth owned by that given percentage of Americans, it is actually possible that the Waltons’ combined wealth was zero or even, for that matter, negative. In other words, when we say that the Waltons have a combined net worth greater than the combined net worth of 30% of Americans, what we may well really be saying is just that around 30% of Americans have a combined net worth of zero. As it turns out here, the source study indicates that in 2007, about 18.6% of Americans had zero or negative net worth, with an additional 11.4% of Americans having a net worth of less than $12,000 (2009 dollars). In other words, these same statistics could be used to say that someone with a net worth of $1 had more wealth than about 30% of Americans in 2007.

Nor was this bottom 18.6% necessarily “poor” in any meaningful sense – it’s going to include renters with car payments, and just about anyone with student loans to pay off, regardless of their income or future income expectations. In other words, that percentage would include a second year associate at a big law firm making $125,000+ a year in salary. Indeed, such a person would have an especially negative net worth.

And, for that matter, it’s not even necessarily true that those who are poor were within this bottom 18.6% – a family on welfare who had a 30 year old, fully paid-for piece of crap car (or no car at all), rented their home, and having ancient, but fully paid-for furniture and maybe a couple of hundred bucks in a bank account somewhere could easily have a positive net worth. Merely by having that positive net worth, they, too, would be “wealthier” by this definition than almost 30% of Americans combined.

In other words, what citing this statistic as “the Waltons are wealthier than 30% of Americans” does is to obfuscate that in 2007 about 18.6% of Americans had negative wealth (apparently the highest percentage for the preceding 25 years, though only slightly higher than in 1995), and that by 2009, thanks to the housing crash, this number likely jumped to a whopping 24.8%. That is itself a very real problem. Moreover, that number had been in the range of 15.5%-18.0% for about 25 years, and in 2004 was just 17%. The 1.6% jump from 2004 to 2007 appears to have been the biggest three year jump since around 1983.

Then the housing crash hit and in 2009 (the last year of data and the year after the crash) it jumped up to 24.8 percent, which appears to be the highest level in at least 50 years.* We don’t know whether or by how much that has increased or decreased since then, but it seems somewhat more likely to have increased than decreased. In an unstable job market, having 25 percent of American households with more liabilities than assets is a recipe for very, very bad things.

Talking about how the Waltons in 2007 had a net worth greater than the combined net worth of 30% of American households when someone with a net worth of a dollar would have had a net worth greater than the combined net worth of perhaps 29 percent is disingenuous and distracts from this much more real and concrete problem of personal debt.

I’m not here dismissing that inequality can in and of itself be a real problem. Nor am I dismissing the notion that there is massive and perhaps unjustifiable economic inequality in this country. But if there is, saying that “the Waltons have more wealth than 30% of Americans combined” has nothing to do with it.

*Emphasis on “appears,” as the paper doesn’t provide data between 1962, when a little over 24% had negative or zero net worth, and 1983, when only 15.5% had negative or zero net worth.

The home that you live in shouldn’t even be counted towards net worth. Logically, you have to sell it to get the value from it, and unless you assume the sellers are going to rent (or live in a shelter…) you have to have another one to move into, which would be a liability.Report

That too. I started to hit on that when I was writing this, but then changed my mind. But suffice to say that it’s highly questionable that the Forbes figures have any meaningful connection to reality for purposes of a comparison with the average person. A huge chunk of that valuation is going to be an appraisal of illiquid assets, and it’s not as if Forbes is sending a trained appraiser in to look at all this stuff.Report

Also, because of that exclusion not being made, a lot of people for whom everything that did count was in the home they lived in were falsely portrayed as being more stable than they turned out once the bottom fell out.Report

Also correct. And therein lies the real problem here.Report

Someone needs to dumb this down for me, because I do not in anyway get it. How is it that your house should not part of your net worth? It is true that you have to sell it in order to have it be liquid – but that’s true of any non-cash asset.

If you have cash and investments of $100,000 and you are underwater $200,000 on your house, you can’t just walk away and keep those other investments – because they were spoken for by your debtor.

THis has got to be one of those cases where I am being really dim, because I don’t even begin to see the argument here.Report

Housing loan is a secured asset; it’s secured by the property.

You absolutely can walk away from a $200,000 mortgage with $100,000 in other assets, as your mortgage company has no claim on them. They have a claim on the house.

Now, on the other hand, if you have another loan that is secured by those assets as collateral…Report

A quibble Pat. This is applicable only in no recourse states of which there are only about half a dozen or so in the US. In most states in the union your lender will sell the house and if the proceeds do not cover the debt they’ll come after you for the difference.Report

Hey, that’s a pretty big quibble and something to my chagrin I didn’t know until 30 seconds ago. I’m surprised New York isn’t on the list. Then again, maybe I’m not.

Anti-Deficiency / Non-Recourse States

Alaska

Arizona

California

Connecticut

Florida

Idaho

Minnesota

North Carolina

North Dakota

Texas

Utah

WashingtonReport

A lot of people don’t know that. I am actually remarkably surprised, with the media reporting on the ethical dilemma of walking away from an underwater mortgage, that people in recourse states aren’t talking up sob stories of losing everything by way of misunderstanding their rights.Report

Of course bankruptcy clears the recourse debt. If you are seriously underwater and unemployed you probably get the ability to cancel the debts. (Under the median income for the area). Note that retirement assets are protected in BK, and perhaps a beater of a car.Report

Anything short of owning the house outright with no payments to make, and it’s a source of debt. Borrowing off it just increases that debt.

Report

You don’t have to sell your home to get value from it; you can also take out a loan to extract equity.

Think of it this way: If you have $100,000 in home equity, you can sell your home and become a renter with $100,000 in the bank. Which means that you’re $100,000 better off than a renter with no assets.Report

I don’t understand. I don’t see Christopher Hitchens mentioned anywhere in this post.Report

My wife and I, DINKS, are way upside down on our home mortgage since the bottom fell out of the market (we bought at the first plateau of the crash, thinking that would be it). But my wife and I make enough money to continue to service the debt and have kept current on those payments. My wife and I both owe more than five figures on our student loans still.

If you were to add up the negative equity on our house and our student loans, it would more than swamp our retirement savings, liquid cash on hand, and the liquidation value of our cars and household possessions.

We are in the bottom 30%.Report

I hear you burt. The hubby and I bought our lil condo on the plateau too.Report

Great post, and one that makes me glad this blog is as diverse as it is, with different people bringing different interests and styles. Tying this into your Q to me in my thread, Burt, I’d say that I don’t really do policy/wonk type blogging — so my writing doesn’t always have a “this means we should…” finish or even subtext. I’m often the most interested in the way people think, and why they think the things they do; what drew me to the 30% stat was how it, if believed, could change the way even an especially pessimistic left-wing class warrior regards the American political scene today. But it’s true that the amount of private debt is the real disaster of the economy right now, and that this should always, always be on our mind when we’re trying to understand the present political economy.Report

Thanks Elias. I appreciate the compliment especially coming from the you, given that you were the person to whom I was most directly responding, even if there have been no shortage of others who have made similar points to yours.

The reality is that the original post everyone linked to for all of this made it really, really easy to reach those conclusions, and didn’t do a good job a showing what data it got from where. If I hadn’t had a rare slow afternoon, I don’t think I would have been able to figure out what the data actually meant and said.Report

Got it. Again, apologies if my inference came off like trying to put words in your mouth.Report

Oh no worries. I don’t actually mind being “castigated” — prolly am a little too liberal with the word — and am of the opinion that if you wanna be a blogger you better be OK with, or even enjoy, knocking heads here and there. Even with ppl you dig!Report

So not only do you write a post addressing most of the points I was going to address, but you do a better job doing it than I would have.

My first thought when reading the figure was that my wife and I have negative wealth… but anyone who calls us poor is being ridiculously literal. As a single guy making $10/hr, I had more wealth than I do married to a doctor making… considerably more than $10/hr.

The second thought was wondering, if we were to confiscate the wealth of the wealthiest of the wealthy and spread it around to the bottom 30% (Hey, we’d be on the receiving end of that! Sign me up!), how much would that come to? I haven’t followed up on my second thought enough to actually do the (probably simple) math.Report

Thanks, Will. Though asking me to do more than add or multiply a small handful of numbers is way beyond my abilities.Report

So, let’s suppose your analysis is correct. If so, then US citizen X with wealth of $12,000 + 1 in 2009 is wealthier than the bottom 30% of of US citizens. On the assumption that the Walton Six actually hold total wealth – assets minus liabilities – than $12,000 + 2, then they are clearly wealthier than citizen X. Maybe wealthier than 31% of Us citizens. But how much more in the ‘+’ column are we to correctly ascribe to the Walton Six (assets minus liabilities)? If it’s in the billions, then doesn’t the conclusion – according to your analysis – not only confirm Elias basic point, but imply that he’s reallyreally understating the relative share of wealth they hold?

Or am I confused on all this?

Report

Actually, it’s that in 2007, a person with net worth of $1 by this metric has more wealth than the combined wealth of 30% of Americans. In 2009, it would be more like 40%. If we’re talking in percentage terms, the Waltons might get an extra percentage point or two, but that’s about it.

In other words, the very statement being touted about the Waltons is almost equally true of someone with a net worth of $1.

Add to that the fact that the metrics Forbes uses for determining net worth are likely to be quite different, and quite more generous, than the metrics used in the consumer survey.

The bigger point is that net worth is a really useless way of measuring inequality. Put it this way: by this metric, a family of four on welfare with a 45 year old head of household would quite possibly be infinitely more wealthy than Burt or I.

And the really, really big point is that this data does show other problems that have little to do with inequality.

Again, none of this is to comment on whether inequality is a real problem with real consequences, a conclusion to which I am increasingly open. It is however to say that this particular study doesn’t tell us much about inequality, and it’s a disservice to use it as such when it does show other quite serious problems.Report

OK. Got it.Report

The bigger point is that net worth is a really useless way of measuring inequality.

It’s a really useless way of measuring inequality if what you’re talking about is people who are within a delta of each other in net worth in comparison to their earning power.

If I’m worth zero, but I have an earning power of $140K a year, I’m in a better ten year position than someone who is also worth zero, but has an earning power of $20K a year.

If I’m worth zero, and I have an earning power of $140K a year, I’m not in a better ten-year position than someone who this year is worth -$10 Million, but has an earning power of $6.7 Million a year.

Generally speaking, for most folks (everybody who is below, say, the 96% in income), the difference between their net worth (asset position) and their income is probably not going to be that great. Maybe a 65 year old about to retire small businessman has a net worth of $5 million on paper (his business, which he is about to sell, minus the few remaining liabilities he is going to unlimber, minus the taxes on the sale of the biz) and his income last year might be $250K. Maybe his 25 year old grandson has a net negative asset position because he just finished his MBA at Harvard, but he’s going to take over grandpa’s business at $200K a year. In absolute wealth, grandpa is way more rich than his grandson, but for practical day to day considerations they probably have within some delta of the same lifestyle.

On the other hand, somebody that is worth a hundred million dollars plus has a cash position that makes both of those guys look – from a relative impact on the economic engine – not all that much different from somebody making $70K a year who isn’t ever going to inherit more than a couple of tens of thousands of dollars.

The hundred millionaire: he’s Jupiter. The millionaire? He’s Neptune. The 70K dude? He’s the Earth. They all qualify as planets, but the hundred millionaire is not the same sort of planet as the 70K dude. The pernicious poor? They’re asteroids, at best, even though there are a lot of ’em. The tens-of-billionaire? They’re stars.

Fundamentally, if you treat all of these objects the same, you’re going to get a very weird system.Report

if you treat all of these objects the same, you’re going to get a very weird system.

Exactly right. There are multiple metrics to evaluate this stuff according to. One is that we’re all in orbit around the same center, and some people are in advantageous positions by default, or thru some other natural processes or consequences. Another is to say that wealth, and income potential (to extend it a bit), are the center around which everything else revolves. Which one is prioritized, or gets preferred consideration, is subject to dispute along pretty standard lines. But to dismiss the data as being innocuous or inevitable by some standard not only misses the important point the data is evidence of, it deliberately and intentionally missed the point.Report

But the point here is that using this data in this particular manner effectively place the person on welfare with a net worth of a few hundred bucks on the same planet as the multi-billionaire. Hell, using this metric, it’s even possible to get someone who makes a billion a year into the negative net worth category.Report

No I get that. But then isn’t the interesting thing about the data that so few people have any accumulated net worth, and don’t have the means to get into the positive category while others clearly and inevitably do?Report

These data don’t really say anything about ability to get into the positive category, though. They do say that there are a lot of people in the negative category, more than there have been for at least 50 years it would seem. That is absolutely significant.Report

Maybe what we’re disputing here is the conclusions actually drawn from the evidence (we both agree on that) and what can be inferred from it. In your view, what would be a reasonable conclusion here? Merely that wealth understood as assets minus liabilities is a useless metric? Or does the data point to other conclusions not explicitly drawn in the paper?

Now, if your argument is merely that billionaires with net-negative wealth are treated as statistically indistinguishable from the mechanic with net negative wealth in the study, then I’d have to concede the point. But is that a reasonable view to hold – that paper billionaires can actually hold net negative wealth?Report

Well, a good chunk of my point here is that the data does point to some other conclusions, and some very serious issues, but that the emphasis on the 30% and the Waltons, which is really a useless comparison, is preventing discussion of those issues.Report

These data don’t really say anything about ability to get into the positive category, though.

That’s absolutely true.

And it only tells us very limited things about what it means to be in the positive category.

Net worth, income, liquid assets, cash position, availability of credit… all of these things taken individually don’t mean all that much when you’re talking about the difference between somebody who makes $0 and is worth $0… somebody who makes $20,000 and is worth $5,000… somebody who makes $70,000 and is worth -$200,000… and someone who makes $250,000 and is worth $5 million… or -$1 million for that matter.

It does, however, tell you that an overwhelming amount of capital is associated with a very small number of agents in the economic system (which, admittedly, we knew already).

When price is supposed to be a negotiated preference, it’s kind of hard to have a meaningful medium of exchange when almost all of that medium is correlated with a very small number of agents.Report

But is that a reasonable view to hold – that paper billionaires can actually hold net negative wealth?

Mr. Stillwater, meet Donald Trump.Report

As handwavey as the study Elias was talking about is (and as Mark points out, it’s pretty handwavey, that’s a fair critique), I think it’s still indicative of a problem.

Big numbers are kind of a hobby of mine. Most people don’t really grok what it means for somebody to have ten million dollars. Ten billion in net worth?

Six orders of magnitude. To put that in perspective… Jupiter’s mass is only 300-odd times that of the Earth… three orders of magnitude. The mass of the freaking sun is 330,000 times that of Earth, that is six orders of magnitude.

Someone who is a tens of billionaire is to Burt – what the Sun is to the Earth.

Now, in celestial mechanics, there’s a reason why we have two different taxonomic classes for those two things…Report

I disagree. The problem with using this as a metric of inequality is that it’s so incredibly easy for the average person to wind up with a negative net worth even if by other measures they would be quite well off, while it’s also not terribly difficult to wind up with a positive net worth even if by most meaningful measures one would be quite poor.

The vastly better metric for wealth inequality would be just to look at assets, though even that would have it’s flaws. There is a reason after all why we usually talk about income inequality rather than wealth inequality- the latter is extraordinarily difficult to measure in a way that makes any real sense, while the latter provides a pretty good picture of actual economic inequality on aggregate (though not necessarily in the specific).Report

I get your point, Mark, and I don’t disagree that it is a very limited observation.

It certainly doesn’t tell us enough to even make an educated guess about policy.Report

Its. Stupid iPad.Report

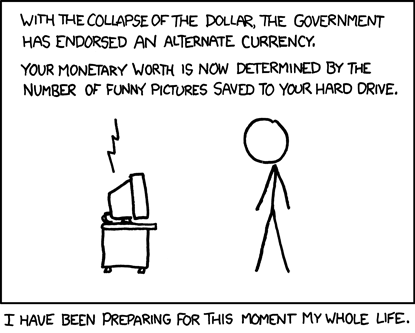

(If the cartoon isn’t visible, you can see it here.)Report

Pithy.Report

Nothing like 1,000 words.Report

I thought it was an intentional meta-comment of zero net worth. I laughed.Report

Indeed. It strikes me as a fairly poor way to explain the whole “wealth” thing.

One thing that is underplayed is the importance of cultural capital and, yes, culture when it comes to wealth. I’ve heard it said that you could take all of the money in the country and distribute it equally… and, in less than a generation, everything would look more or less like it does now.Report

Cultural capital does indeedy matter quite a bit.

That grandson of the small business man has a lot more cultural capital than the average $70k/year fella will.

On the other hand, just about anybody can earn cultural capital pretty fast. You just need to get out there and plug into it.Report

Spoken like someone who gets along with people.Report

How else can one further his nefarious plots?Report

No fair! I was going to post that! But then I was going to post this: Report

Report

In Louisiana there are two things that the government did that really helps. There is the homestead exemption tax that does not charge taxes (I think) on the first 150,000 on your house so property taxes for us amount to 150 a year. The other thing is a program called TOPS that pays most of in state tuition for college. So except for our daughter that went to nursing school while in the national guard and was called out three times, once for Katrina and twice so President Bush could kill Sadam, none of our children got out of college with large debts. One was offered a half scholarship to Duke, but when she added the total cost said no thank you.

If anybody is interested there is a good article about Walmart’s employees and their cost to California taxpayers because they make so little money at “Facts in the Walmart documentary”.

We were very lucky down here because while property went up some, it was not near as ridiculous as in other places. Another reason we are lucky is that my wife worked as a loan officer in a bank and it is impossible to bs her and so our loans were the best one could get. Plus, since I am a carpenter our house was really cheap to build. We don’t make much, but everything is paid for so I guess I am richer than thirty percent. Our biggest monthly bill is car insurance.

Report

I came back to Baton Rouge after five years on the road. In 2002 and 2003, thing were looking good in Louisiana. I made friends south of Interstate 10 in Cajun country: my African French converted to Cajun with a few accent modifications and I have a standing offer to teach French in Abbeville.

I drove from Phoenix to Baton Rouge along the back roads, coming south from Shreveport and Alexandria through to Mamou, back to Lafayette and Baton Rouge. I spent some four months there, looking into starting a cattle operation south of Lafayette and trying to find solid work in software. I could have gone to New Orleans, which I ultimately refused to do. I eventually came north, to Minneapolis, simply because there was work, that and to to be with my girlfriend who’d traveled with me all that way. I now live in a tiny town east of Eau Claire, starting a software consulting practice. There’s work here.

How I’d hoped things would work out in Louisiana. I came back to a hotel I’d known well. It was a wretched shadow of its former self, half-wrecked by the Yats come up as refugees from Katrina. The malls were ghosts of their former glory and not even Blue Cross Blue Shield of Louisiana had any work for me, though they remembered me with considerable kindness.

I’d still love to return but that’s not likely in the cards, at least the cards I have been dealt. Though land is cheap in Louisiana, there’s a reason why.Report

Renters don’t necessarily have lower net worth than homeowners. Especially nowadays, when many homeowners have negative equity in their homes.Report

@Patrick If big numbers are a hobby of yours you ought to really enjoy this.Report

Already ordered my copy. I’m a daily XKCD reader.Report

If you like that one, Ward, you might like this one, too. It’s very well done.Report

If the pay of people in the lowest echelons had grown at even half the level the pay of people in the highest echelons had grown, wouldn’t personal debt conceivably be much less of a problem (what with people actually having the ability to pay their debts)?

Report

Possibly, but saying “the Waltons have more wealth than 30% of Americans” doesn’t tell you anything about that.Report

Sure it does. It tells you that the Waltons have an epic amount of money and that a lot of other Americans don’t. The idea of an eye-popping statistic like this – even if it has been calculated poorly – is to get Americans to look at the current economic structure and boggle about how wildly unfair it has treated vast swathes of the American populace while benefitting outrageously a select few. Numbers like these are, essentially, bait.Report

The first Forbes 400 list in 1982 had 28 members of the Du Pont family. Today, none.Report

In other words, they’re useful because they scare people even though they don’t actually withstand any kind of factual inquiry.Report

Do the Walton’s have billions? Yes.

Do millions of Americans not have billions? Yes.

Has the study here been built on shaky ground? Yes.

Does the point still stand though, the one about a select few controlling huge amounts of wealthy while millions have little? Yes, absolutely.

Facts like these don’t, incidentally, scare people. They’re as I said: bait. They’re designed to get attention. They’re designed to make people realize how vast the gulf is between the wealthy and everybody else.

Report

…except that the fact at issue here does not actually show a vast gulf between the Waltons and everyone else, and that’s the whole point! The same statement is almost equally true of someone on welfare as it is about the Waltons! That doesn’t change whether there is a vast gulf between the Waltons and everyone else, nor do I even attempt to deny that other facts do show such a gap. Hell, I’m even sympathetic to the notion that inequality is a real problem in and of itself.

But I’m not a big fan of, in effect, lying to promote that notion, especially when it comes at the expense of discussing other potentially serious problems.Report

That depends on whether people are in debt because they objectively don’t have enough money to get by, or because they have a tendency to spend money as fast as or faster than it comes in.

I suspect the latter.Report

I suspect this is a very complicated question.

If you heavily suspect the latter, is it because you’ve done some research or is this just going with your gut?Report

For some it’s the former, for some it’s the latter, but for no small number it’s neither – it’s that they took out loans as investments for their future, whether to buy a house or to pay for their education or buy a car to get them to work, and they are effectively underwater on those loans. For some, that is a major problem, for others, not so much.Report

New rule: Before I post (sparingly to be sure) I should check more diligently to see if you’ve made the basic point I’d thought of sooner, better, or both (as in this case).

Good post Mark.

Generally, I find that numbers and statistics increasingly obscure and inhibit important discussions about important topics more than they make them richer and more lively.Report

Kyle! Good to see you around!Report