All photos from Wikimedia Commons unless otherwise noted in caption.

The Mother of All Ditches

In the beginning, there was a ditch. It ran from a bend in a short nearby river through a village with the cumbersome name of El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora La Reina de Los Angeles sobre el Rio Porciuncula.[1]

The Zanja Madre (“Mother Ditch”) was the backbone of the city from its start. Los Angeles had been planned from the start: a Spanish nobleman, Felipe de Neve, had read classical literature and was moved by the Romans’ ideas about central plazas, grid-shaped city street networks, and inflow and outflow of water. So when he became the fourth Royal Governor of California, de Neve became Los Angeles’ first civic promoter, laying down plans for a future city and working hard to attract wealthy investors and hopeful workers to come to the pueblos he founded in the name of Carlos III.[2]

The man in charge of overseeing the water supply for the new town was called the Zanjero, the “Ditch Man.” Today, the Zanja Madre can be traced from the historical park where the old Pueblo was located near Los Angeles’ Union Station up through the Gold Line of Los Angeles’ metrorail, up to the point that the train crosses the now channelized river.

History happened. The pueblo bloomed, growing from eighteen colonists to nearly a thousand. Spainish Alta California became part of Mexico, and after some very strange skirmishing in 1846, the United States took nominal control of California after about a week of nominal independence. The Treaty of Cahuenga was signed on January 13, 1847 in what is today a park in North Hollywood, of which most Angelenos are disinterested, ending the fighting in Alta California. A year later, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended the war with Mexico and Los Angeles became part of the United States of America.

Water Law Shapes The City

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo also contained a term protecting “pueblo rights,” which provide that settlements created under the Spanish or Mexican governments retain the right to use all the water in streams and rivers flowing through their boundaries. Unlike all other water rights in California, these rights cannot be lost through disuse, nor may they be transferred. Discussed from time to time but never formally invoked until the 1970’s, pueblo rights meant that the city of Los Angeles controlled all of the water in the Los Angeles River, both surface and subterranean.

After becoming part of the United States, California adopted the riparian rights doctrine for most water usage. Bear in mind that water flowing through surface streams and underground aquifers is a public good, not owned by anyone, but the right to take that water is one that belongs to someone. So in a riparian rights regime as prevailed in the early days of California’s statehood, any landowner whose land includes or adjoins water might divert it to her own use and no one downstream has the right to complain about it.

So, the water rights in Los Angeles rested on paper with the fledgling city. A private company which came to be known as the Los Angeles Water Company administered Los Angeles’ riparian water rights from shortly after the end of the Mexican war until 1902.

But evolving at the turn of the twentieth century was a special legal doctrine in called appropriative rights, a hybrid of the law of adverse possession appropriate to a frontier state seeking to use the law to encourage development. An appropriative right gives the ability to secure extraction rights to a person who had been using that water for “a reasonable and useful purpose” for at least five years before claiming the right. In order to get this right to use water, one has to “exploit” it – to physically take the water, whether rightfully or not, and then to use that water in some way, such as for agriculture, industry, or in this case, for distribution for municipal use.

It would not be until after the climax of our story here that water rights would become codified in the Water Code of 1914, which has been tinkered and modified with by the legislature and courts on a more or less continuous basis ever since. Today, California’s Water Code is one of the longest and most intricate pieces of law in the English language.

The legal landscape of the pre-Code California worked well enough for a small city like Los Angeles, but soon enough, the frustrated leaders of this small city came to realize that without more water, they would remain the leaders of a small city. They needed access to more physical water, and they needed enough political cover so that the law would protect their actually taking it.

What they needed was a hero, a hero who came in the form of a civil engineer.

A Man on the Move Takes A Job and a Man on the Make Goes Camping

William Mulholland had gotten out of an unhappy family situation in Belfast, Ireland by joining a British Merchant Navy which did not care much that he had never completed grade school. In 1877 and after four years at sea, the 21-year-old man alighted in what was then a city of less than ten thousand souls. There were some nice houses, a small urban core of about a dozen multi-story office and apartment buildings, bean and nut farms, oil fields, and cattle ranches.

He’d been hoping for more. Unimpressed by what he saw, he thought to get on the next ship that needed a hand going up to the better-developed area around the San Francisco Bay, but needed some money in the meantime. So he took a job as a zanjero, digging wells and ditches. Fatefully, the man who hired him, the superintendent of the Los Angeles City Water Company, was Frederick Eaton.

Though he’d never had much formal education, Mulholland was both intelligent and energetic. He lived in a shack north of the city near what is today the Lincoln Park neighborhood to better oversee the construction of diversion channels and penstocks to replace the old water wheel, and the creation of an underground catchment to get at ground water.

Photograph by the author, August 12, 2012.

By 1886, Mulholland had taken Eaton’s place as the superintendent of the Los Angeles Water Company. Eaton became mayor of Los Angeles in 1898, in part after organizing an effort to transform the water concessionaire into a public utility.[3] For a vacation after his two-year term expired, he “went camping” in the Owens Valley, below the eastern face of the Sierra Nevada Mountains.

It wasn’t really a “vacation.” He took maps provided to him by one J.B. Lippencott of the Federal Bureau of Reclamation, and when he returned, he took a meeting with Mulholland. Mulholland went to the Owens Valley himself, on “company time,” and did his own survey.

A Buyer’s Market

Very soon after his return, a campaign of the creation of dummy corporations and straw buyers up and down the Owens Valley began, orchestrated and headed by Eaton. By then out of office, Eaton purchased quite a lot of land in his own name and quite a lot through a variety of other fronts. Unable to conceal his own political celebrity, Eaton professed a desire to retire to that portion of the country and raise cattle. Eventually, the facades were set aside and it became clear that what was really being bought up, bit by bit, were the water rights for the entire region, stretching over two hundred miles of sparsely-populated farm and ranch land.

The degree to which Eaton, Mulholland, and their associates concealed their true intentions from the sellers of the land and the residents of Los Angeles was then, and still is, the subject of a great deal of controversy.

Apologists for the effort, including Mulholland’s granddaughter and biographer, insist that there was no secret made that water rights were being purchased, and purchased so that the water could be moved elsewhere.

But the fact that Eaton and a few other land commissioners were able to sell property they had bought in the Owens Valley to the city of Los Angeles at very handsome personal profits does not add luster to the notion that all business had been conducted strictly on the up-and-up. The treble participation of one J.B. Lippencott on the aqueduct’s planning committees, the U.S. Board of Reclamation, and in the financial control group buying up all the land along with a veritable who’s who from the Los Angeles Thomas Guide, with names like Edward Doheny, Henry Huntington, Harrison Gray Otis, Harry Chandler, Henry O’Melveny, stank to high heaven.

The legend of the insider-information land swindles was powerful, powerful enough to spark impromptu domestic terrorism and at least one legendary motion picture.

The Fortunate Drought

Los Angeles experienced a significant drought from 1893 through 1904, over which time the city’s population roughly doubled. In 1904, Mulholland allowed himself to be interviewed by the Los Angeles Times and predicted that these trends were about to end: the city would not grow much beyond its then-present size of 100,000, because there simply was not enough water locally to sustain more life than that.[4]

There are accusations that with Mulholland’s a) instruction, b) connivance, or c) negligence, river water was run directly into the sewers and put out to sea so at to enhance the drought, and still others suggest that d) no, this never actually happened, that however much Mulholland wanted to build the aqueduct, he would not have endangered lives that way.

About whether Mulholland manipulated water flows to make the drought seem worse than it was, I am agnostic. What is clear is that the voters of Los Angeles got good and scared, and passed a bond initiative for $22.5 million–the equivalent of six hundred million dollars today–to build an aqueduct the likes of which the world had never seen before. It was the most expensive and ambitious public works project that had ever been undertaken by a city.[5]

Digging A Ditch Uphill

Thus began construction of the Los Angeles Aqueduct. Mulholland’s surveys of the territory, combined with his natural aptitude for engineering, produced 233 miles of water channel. 43 men died during its creation. Over thirty million gallons of concrete were poured. The southern Kern County backwater of Mojave turned into a boom town, with the largest industry not being mining but rather prostitution, so as to service all the construction workers.

Mulholland is famous for this feat of engineering, and rightly so. The aqueduct collects the headwaters of the Owens River near Bishop in open ditches, runs them down a concrete channel along the base of the Sierras, then starting at a place near the Alabama Hills the water is diverted into a very large pipe that moves across the Mojave Desert and over three mountain ranges. A gasoline-powered tractor known as a “caterpillar” was invented for the job, and legend has it that Mulholland gave the device that name himself.

Photograph from Historical Photo Collection of the Department of Water and Power, City of Los Angeles.

It is entirely gravity-driven, which is a little hard to believe when you drive highway 395 and see the pipe moving up the side of canyons. But Mulholland had learned a trick moves water up hills with nothing but gravity and water pressure. He made the water in his ditch flow up hills and towards money.

What is less well-known about the five-year effort to build the aqueduct is how much time Mulholland spent in New York, Boston, and Philadelphia trying to get money to build it. Though the City of Los Angeles had approved very generous bond measures to build the aqueduct, funding those bonds was something different entirely. Mulholland had to convince skeptical bankers that it was physically possible to build an aqueduct nearly 250 miles through the desert, legally possible keep all the water for the destination free from interference, and economically possible for the city’s landowners to buy enough water at a high enough rate to let the city pay back the bonds at the promised interest rate. Three times over the five-year construction, the effort nearly failed because the city could not raise enough funds fast enough.

But finally, on November 5, 1913, water began flowing down the Santa Susanna Mountains and into the area known today as Sylmar. Mulholland had fallen ill with the flu on the day that would crown his career and create a metropolis. So he turned one of the cranks to lift the sluice, and let loose the torrent, calling out to a crowd of nearly a third of the entire city gathered to watch the event: “There it is. Take it.”

He probably couldn’t have said much more than that, given that the crowd rushed forward to the channel with cups and glasses, to take their first taste of Los Angeles’ future.

Surplus and the Law: Why Los Angeles Is So Damn Big

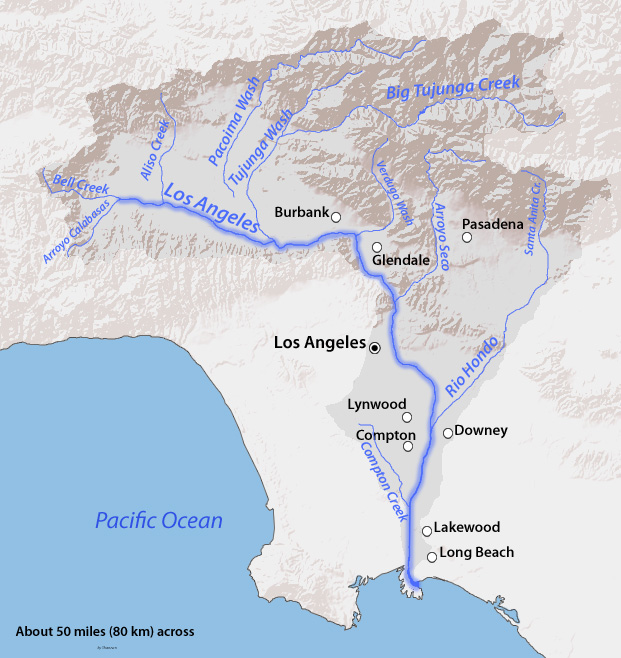

Initially, there was more water than the city could use – nearly four times as much. After all, the local water from what was by then known as the Los Angeles River, and the groundwater, didn’t go away. But the law – the confluence of the pueblo rights from the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, the riparian rights to the local waters and the purchased riparian rights in the Eastern Sierra, and the appropriative rights to the Owens River waters resulting from the creation of the aqueduct, was such that Los Angeles could not share its water with any other city lest it lose its legal rights to that water for the future.

Largely unnoticed in the contemplation of the scariness of the turn-of-the-century drought, and the scariness of the massive bond issue, was what is today section 104(c) of the Los Angeles City Charter. The City had bound its own hands, and more importantly bound its future leaders’ hands, from ever selling any of its water rights to any other person or entity without a two-thirds vote of the city’s electorate. This effectively prevented water rights from going to anyone or anything else other than the city.

Indeed, the city refused to even sell the physical water to other local cities, lest they acquire some form of the still-evolving appropriative rights to water. As it turned out, that would not have happened because appropriative rights do not apply to imported water (like the aqueduct’s water) which is then sold to non-importers — but that the law would work out this way was not clear in 1913. So Los Angeles held on to its water, jealously refusing to sell a drop of it to any of its neighbors.

The solution was for those other local communities to join Los Angeles. In 1900, Los Angeles had under 100,000 people and was about 50 square miles. The major local industries were agriculture, shipping, and oil extraction. But in order to get at the cheap and plentiful water, local communities offered themselves to annexation. By 1930, Los Angeles was 450 square miles in size was the fifth most populous city in the country.

Boom Town: The Aftermath

All of which meant that Mulholland’s predictions of imminent drought and insufficient water supplies became a new cycle of the city’s existence. Los Angeles’ growth came from the development that the water made possible, the laws that propelled it to grow so as to keep the water propelled it to use the water, sometimes wastefully, but never by anyone but an Angeleno. Which launched a cycle of boom growth ceasing, water panic, water acquisition, and boom growth renewing. Not ten years after the Los Angeles Aqueduct was completed, Mulholland was looking to the Colorado River, and also to create dams in the hinterlands of the booming city.

For more than a decade, William Mulholland was the toast of the town. He could hardly not be – he’d made everyone who was anyone fantastically rich. (He did all right for himself, too.) He’d put Los Angeles on the map, not just of the country but of the world. He served as a consultant for the construction of the Panama Canal and for the aqueducts that watered New York and San Francisco. The University of California gave him an honorary doctorate. He was introduced at one black tie event after another with “What can I say, he’s Bill Mulholland,” and the highest street in the city with the most commanding view of its growing expanse named for him, he was asked repeatedly to run for Mayor and amusingly responded that he would prefer to give birth to a porcupine, backwards.

Sadly and tragically, Mulholland’s career came to an abrupt end in 1928, when a dam he had arranged to be built, and which he had personally inspected not twelve hours before, collapsed suddenly and disgorged the entire contents of the San Francisquito Canyon Reservoir in a 55-foot high wave on the town of Santa Paula, killing over 600 people. Mulholland took immediate and complete personal responsibility and after participating in the investigations and (with some controversy) being cleared of criminal culpability, retired from public life altogether.

Nevertheless, Los Angeles got its dams and it got all the aquifers feeding into its river. It got more water from other parts of the state with the California Water Project built principally by Governor Pat Brown, the father of California’s current Governor, who called it an attempt to reconcile population and geography. It got its water from the Colorado River — indeed, its accretion of neighboring cities only ended when those cities banded together with nearby counties to form their own water district to “go in halfsies” on the Colorado River Aqueduct with the LADWP (unable to say no to Colorado River water, Los Angeles subsequently joined this water district). And it built a second aqueduct to the Sierras, completed in 1970, which reaches as far north as Mono Lake.

It is this second Owens Valley aqueduct’s cascade that one can see driving north out of the city along Interstate 5, snaking its way gracefully down the San Gabriel Mountains and making the existence of the metropolis below possible. Where once it offered four times the water the city needed, Mulholland’s aqueduct today supplies about 16% of the water consumed by the three and a half million people who live in Los Angeles, which is the anchor for the world’s thirteenth-largest metropolitan area.

The Evitability of Los Angeles

If not for Fred Eaton and William Mulholland meeting in late 1877, would Los Angeles have ever become the massive city it is today? Its growth into United States’ second-largest city (and the world’s thirteenth-largest metropolitan area) seems a massive, inevitable fact today.

The discovery of gold near Sacramento and the superb natural harbor of the San Francisco Bay may have made the urban development of those areas inevitable. But it took a massive act of will, money, and labor in order to divert enough water to the Los Angeles Basin so as to allow a city of more than the 300,000 or so the river and its associated ground water would support to exist there.

When Mulholland arrived, Los Angeles’ principal industries were agriculture and oil extraction. A living example of another city supported principally by agriculture and oil extraction in California exists in reality and nearby: Bakersfield. When Mulholland got there, Los Angeles had a population of about eleven thousand; by the time he took over and began thinking about the aqueduct, it had grown to about 100,000; by the time he was done watering his city, it was a million and a half. To say that Bakersfield grew more slowly and not nearly as large is something of an understatement.

Not to slight the good people of that fine city, but Bakersfield is not exactly the same sort of city that Los Angeles is today. In 1900 they were not all that dissimilar from one another. Today, Bakersfield is fundamentally the same city of oil pumping and agriculture it was a century ago. Its contemporary civic center even looks a little bit today like Los Angeles did in the 1910’s, allowing for updates in architectural style over the years. It strikes me as entirely plausible to think that Los Angeles could have evolved into a city very much like its smaller cousin to the north.

Photograph from Los Angeles Times.

It seems that for most people, infrastructure and the weight of choices made by past generations are invisible and inconsequential. But I see them, every day. I live very near the most sensitive place in all of California: the point where the Los Angeles Aqueduct crosses the California Aqueduct. I work with lawyers who adjudicate water rights. I’ve perused (microfiched copies of) land grants with the names of Kings of Spain and the governors whose names adorn our streets. I’ve dealt with clients and travelled up and down the Owens Valley, hearing all sorts of stories and legends about Eaton and Lippencott and both spitting-bitter curses and hero-worship aimed at Mulholland. This history is alive to me, alive and keeping my state, my city, my existence possible every day.

It was not inevitable that Los Angeles be what it is today. It could have been beans, cattle, and oil derricks, like her smaller cousin city to her north. Mulholland is portrayed in history as a heroic figure and sometimes a tragic one, but he let himself get involved with some genuinely murky and almost certainly corrupt men, most prominently Eaton and Lippencott so it is best to consider him a morally ambiguous character rather than either a hero or a goat. But saint or villain, his ingenuity and industry changed history. One hundred years ago today, William Mulholland stepped his city up to the big time.

Happy anniversary, Los Angeles.

Sources:[6]

Davis, M. (1992) City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles. New York, NY: Vintage Books. ISBN 0-679-73806-1.

Littleworth, A.L. & Garner, E.L. (2007) California Water II. Point Arena, CA: Solano Press Books. ISBN 978-0-923956-75-2.

Mulholland, C. (2000). William Mulholland and the Rise of Los Angeles. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-585389-96-7.

Reisner, M. (1993) Cadillac Desert: The American West and its Disappearing Water. New York, NY: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14

[1] Ponder for a moment the accident of linguistics that resulted in the diminutive name for this city being “Los Angeles” rather than “Rio Porciuncula.” Basketball fans could have found themselves chanting “Beat R.P.! Beat R.P.!” every time the Lakers played a close game.

[2] If you pay attention in your travels throughout California, you can see the names of California’s more influential Spanish and Mexican Governors in the street names in our major cities – Portola, Argüello, Carrillo, Pico, Figueroa, Castro, Alvarado, Micheltorena – but these are just names that don’t mean much of anything to most Californians. Even amongst these men condemned to obscurity, de Neve is particularly lost to the fog of time: I’ve never seen a “De Neve Street” or a “De Neve Park” anywhere. A branch of the Los Angeles City Library and a dorm building at UCLA are the only civic references to de Neve that I can find within the city that he founded.

[3] This finally happened in 1902, two years Eaton had left office, as a cost of two million dollars. Lobbying for taking the water company public was Mulholland’s first foray into politics, and publicly he registered formal opposition to the idea, but he let his friends know that actually he thought Eaton’s idea was in the public interest. At the time Los Angeles’ population was a little bit over one hundred thousand people, less than a third the population of San Francisco and ranking it as the thirty-sixth largest city in the United States. Two million dollars in 1902 would be worth approximately fifty million dollars today.

[4] Privately, estimates both then and now were that the Los Angeles River and its associated ground water could support a population of about 300,000.

[5] But in fairness, not the most expensive or ambitious public works project undertaken that year.

[6] Sources listed are only those not hyperlinked within the article itself.

Burt Likko is the pseudonym of an attorney in Southern California. His interests include Constitutional law with a special interest in law relating to the concept of separation of church and state, cooking, good wine, and bad science fiction movies. Follow his sporadic Tweets at @burtlikko, and his Flipboard at Burt Likko.

Burt Likko is the pseudonym of an attorney in Southern California. His interests include Constitutional law with a special interest in law relating to the concept of separation of church and state, cooking, good wine, and bad science fiction movies. Follow his sporadic Tweets at @burtlikko, and his Flipboard at Burt Likko.

A magnificent piece Mr. Likko.

The one other big difference between Los Angeles and Bakersfield is that the (old town of the) former is only 25 miles and no mountain passes from the ocean. On the other hand, neither the Port of LA nor the Port of Long Beach are natural harbors, and their development into the premier west coast container facilities is directly related to having a huge metro area appended onto them. On the other other hand, California has a dearth of natural harbors between the San Diego and San Francisco Bays, so building something at San Pedro Bay is probably as good as anywhere. (though in this scenario, San Pedro would have likely been a ‘twin city’ to LA. )Report

Thank you, @kolohe .

It may seem a mystery why San Diego did not become Alta California’s premier city during Spanish and Mexican administration. It has a magnificent natural harbor and plenty of good land for crops and cattle. The answer (I think) is that the San Diego River was unstable and unreliable, switching channels and periodically running dry. The nearest stable river, the Tijuana, was too far away to be routed through canals or ditches to the area near San Diego’s harbor using eighteenth-century technology and the minimal manpower available. But Felipe de Neve, one of the first governors to actually look to urban development of the area, chartered three pueblos in Alta California: Los Angeles, Santa Barbara, and San Jose. De Neve found San Diego lacking for some reason, and I think it was the unreliability of the fresh water source.

Also of note to your point about ports factoring in to development and growth: the Spanish and early Mexican governments thought that Santa Barbara was riper for development and growth than Los Angeles: deeper water right offshore, greater military defensibility, moister and more stable climate, possibly better soil and good cattle country in its hinterlands. The greater distance involved and the relative dearth of flat, developable land as compared to Los Angeles makes the idea of a Santa Barbara-centered California relatively implausible, but it apparently didn’t seem that way to the seventeenth-and eighteenth-century leaders of Alta California.

Of course, the world-class natural harbors of the San Francisco Bay were responsible for that area being the foci of the development that actually happened. If I had been betting on cities to take the lead in California in 1750, my money would have been on San Jose: lots of land, an easily-expoitable river, the Bay right there for easy commerce with Spanish holdings in south America and the south Pacific.Report

wiki tells me that the San Diego mission and pueblo pre-dates the Los Angeles (& the San Gabriel) one(s). wiki also tells me that there was a complex interplay of the Crown, the Church, imperial administrators, settlers, administration zones, two different Church orders, ongoing battles with the aboriginal population, and yes, water, that gave the Los Angeles a somewhat superior political and economic (and population) position to San Diego (but both vastly inferior to San Francisco) by the time of Mexican Independence, and later, the annexation by the USA.

However, I don’t put much stock in prescient planning for 17th to early 19th century european colonization locales. There is a vast cottage industry (in some cases literally) on the east coast of North America based on being a place that used to be someplace.

I was thinking more how late 20th century development would have occurred were LA hampered (either politically or technically) in its early 20th century efforts to expand that you detailed in your post. My guess is that it still, nonetheless, would have been growth deferred, vice growth denied. I can’t think of a better place where the combo of the sunshine and the regulatory environment would enable the de facto world headquarters of the visual mass media industry. The same factors make it almost inevitable for the aerospace industry to be a big player in Southern California. Plus, just with weather, the automobile, and the jet, it seems likely that the Los Angeles Basin would have grown as quickly, if not more rapidly (due to even more favorable conditions) as the Phoenix metro area has since the 60’s.Report

I will do a more serious read but whenever I think of water in LA, I think of Roman Polanski’s Chinatown.

What this says about me…..Report

Chinatown is the genesis myth of Los Angeles, no question about it. While there’s no evidence Fred Eaton was not guilty of the particular kinds of interpersonal monstrosities as the villain in that movie, I can’t acquit him of the corruption. He and the rest of the early elite made out like arbitrageurs speculating on land in the San Fernando Valley and there’s little doubt that they were willing to use sharp tactics to make sure they succeeded at it.

The ambiguity is the degree to which Mulholland, the heroic engineer, participated. On the one hand, he really did see himself as a public servant and really did care about the public interest, and at times acted consistently with this, never more so than when he responded to the disaster in San Francisquito Canyon with political seppuku. On the other hand, he bought and sold all kinds of land too, and at minimum was willing to turn a blind eye to what he must have known his associates were up to.Report

And is there any evidence that Eaton was guilty of interpersonal monstrosities? 🙂

Fantastic job, counsellor. Rather than San Jose, my ca 1750 bet for the future capital would have been someplace like Benicia (which was of course briefly the capital), anticipating that the economic anchor would have been transshipment from riverine (agricultural products) to oceanborne (New Orleans model) and that the local land logistics of San Francisco would have been too limiting. Report

Ack! I meant to acquit him, not condemn him! FTR, it is reasonable to suspect Eaton of plentiful acts of land fraud and public corruption. But not [vaprfg-encr]; all accounts I’ve read of him suggest [n erznexnoyl qhyy snzvyl yvsr]. Wait, everyone’s seen Chinatown already, right; need I rot13 the spoilers?

I agree that Benecia or Vallejo would have been reasonable bets at one time, too — somewhere right there at the mouth of the delta.Report

Fascinating Burt, well done!Report

Echoing Kolohe, a maginificent essay on an endlessly fascinating topic.

And you’ve done me a great service. I am guest teaching a couple of lectures next term in an interdisciplinary honors course called simply “Water,” that will have students studying water from scientific, political, legal, literary, and religious perspectives. I may have just been handed an excellent reading for one of my guest talks.Report

J @jm3z-aitch , I am assuming you have read Cadillac Dessert? If not, I think it is right there for you.Report

Aaron,

Yes, but years ago. Many flashbacks while reading Burt’s essay, especially about the San Francisquito Dam collapse (I’ve been up to the spot), and it would definitely be on my research list. But Burt’s essay is a quicker read. 😉

I’m still waiting to hear what the person coordinating the class wants me to give guest lectures on. I pitched him several ideas, and don’t know know which ones he’ll bite on (it depends in part on what other faculty offer him, as well). So I don’t know if this topic will make the cut.Report

Very impressive.

A few nits: Your treatment of subterranean waters. Pueblo rights, iirc, attach to subterranean rivers (ie, within the bed and banks of a definable river). Groundwater, by contrast, is owned by the landowner above. The problems associated with groundwater management have lead to the “adjudication” of groundwater basins and the formation of limited-power governmental agencies known as water districts. (Some of these have been notoriously corrupt.) But successful groundwater management has been a key element of LA’s ongoing ability to provide meet demand.

Also, I thought that LA was a founding member of MWD. There’s a whole another story (or two) about the Colorado River, including building Hoover Dam and sending its power to LA.

(I also used to be a water lawyer. That practice collapsed in the recession — no more development meant no more need to find new water.)Report

And one more thing — the huge pipelines you see to the west of the I-5 just north of the Grapevine are the West Branch of the State Water Project. Here’s a pretty good photo.Report

I had some assistance from a colleague involved in ongoing groundwater adjudication. And editorial help from Ordinary Times colleagues Michelle Togut and Vikram Bath. All have my thanks. Any errors in the piece are entirely my own.

Is the large cascade draining into the Sylmar Reservoir a SWP/MWD or DWP facility? I don’t think I specifically mentioned the uphill pipes at the Grapevine, although they are also impressive feats of civil engineering and I note that they, too, make water flow towards money.Report

Burt,

I thought the large cascade was the outflow from the Grapevine pumps (for those not in the know, a tremendous engineering feat that pumps water over 3,000 feet up an over the transverse mountain range caused by the bend in the San Andreas fault). But in retrospect I think I’m wrong, because that water flows into Castaic Lake (in my wife’s hometown), and then into the wash that flows behind their house, which I think feeds into the L.A. river. So your original claim maybe sounds right to me now.Report

“Ongoing groundwater adjudication” is redundant; none of them ever end. Given your geographical location, though, I’ll bet your colleague is involved in the Antelope Valley Adjudication. I was peripherally involved in that case.

Sylmar Reservoir is solely a DWP facility. But as this map shows, the LA aqueduct never goes over the Tehachapis. The aqueduct is nestled against the southern edge of that mountain range. The California Aqueduct comes straight down the Central Valley. The West Branch of the California Aqueduct is lifted over the Tehachapis by the Edmonston Pumping Plant, and that’s what you can see from the I-5 freeway north of the Grapevine (which, for all the non-Angelenos is the name of pass over the Tehachapi Mountains, found to the north of Los Angeles).

After crossing the Tehachapis, the West Branch terminates in Pyramid Lake, which in turn delivers the water into Castaic Lake, which is a state (Department of Water Resources) facility. Water is then delivered to individual State Water Project contractors. I believe that only Castaic Lake Water Agency and MWD physically draw from Castaic Lake.

A map and list of SWP Contractors and their annual allocations can be found here. But that’s an old document; allocations have changed since then.Report

Speaking of errors in your piece (there aren’t really any), how is it that you got so much of what’s an incredibly complicated situation correct in this piece, and yet in early October managed to lose three or four major irrigation systems in an answer to the trivia quiz?

for heavens sake you dropped both the Colorado River Aqueduct and the Central Valley Project in your answer and you had the All-American Canal running all the way to San Diego!

Is there really just one Burt Likko? Three weeks is not that long to go from where you were then to where you are today.Report

Methinks you credit me with having invested greater effort into a Monday Trivia answer than would be strictly accurate, @francis . IIRC, I was sitting in a jury box between short-cause trial calls and might have had portions of my mind focused elsewhere. Absent-mindedness is demonstrated in, inter alia, having overlooked that California takes water from the Colorado River and it has to somehow get to the coastal cities from the Arizona border. 🙂

But this piece, I researched. I originally developed a more ambitious thesis about how the law impelled the rapid growth of Los Angeles’s political boundaries and economic development. After a little digging in, I realized that that my own knowledge of the legal landscape would not be complete enough to defend such a proposition. So I did what a lawyer ought to do in such situations: I asked a subject matter expert for help. And lo! Right there in my office was a lawyer involved in groundwater litigation, who is entrusted with knowledge of my secret bloggy identity and enjoys lurking on these pages from time to time.

My colleague (who recognized you from your comments, and he speaks well of you) generously took some time reading an early draft of this piece and gently informed me that I’d gone too far out on the limb. He gave me access to his water law library (the book by the BB&K guys was pretty good) and patiently explained why the bigger-picture legal doctrines like pueblo rights and appropriative rights were not nearly so important to this subject as Los Angeles amending its own charter.

The extent to which I have accurately conveyed both the legal and logistical situations is the product of other people’s efforts to educate me, kicking and screaming at times, away from my prejudices and into reality.Report

So, having given us the definitive LA Aqueduct post, when do we get the Colorado River / 7 States / Hoover Dam / Law of the River / Colorado River Aqueduct / Salton Sea post?

(I’m sure you’ve learned that water from the Colorado River gets to San Diego via the Colorado River Aqueduct, not the All-American Canal. [The San Jacinto mountain range being in the way.] And, a decade after the Quantification Settlement Agreements were signed that transferred a portion of IID’s rights to San Diego, those agreements were upheld just a few months ago.)

or the State Water Project / Bay-Delta post?

or the Central Valley Project (with a subsection on Kesterson?

Come on, you’re just getting started! You live in the most hydraulically complex society that (likely) has ever existed! Even Roman engineers would be impressed by what we’ve done.

😉Report

Colorado is slowly gearing up to address the problem of linkages between ground water and surface water. Let’s see if I can remember the details w/o looking them up. Colorado’s share of the Republican River flow is grossly over-appropriated, so holders of junior rights get little water in some years. Many “newer” farmers were never going to get river water, so started drilling wells and drawing on the underlying aquifer. Holders of junior rights to the surface water have now sued, on the grounds that there is a hydrologic linkage between the river and the aquifer, so that lowering the aquifer level reduces the river flow and deprives the junior rights holders of water they would get in the absence of the wells.

Right now we’re in the early phases of dueling experts. A couple of years back the legislature killed a bill in committee that would have set up rules, giving as a reason that it would be some time until the “facts” were sufficiently settled to consider the policy question. Given that it’s a western water law case, I anticipate that they’ll settle things in 20-25 years :^)Report

To read more about the story of Hoover Dam and its link to the Imperial Valley see Colossus which is the story of how Hover Dam first got authorized and then how it was built. Back in the early 1920s no one trusted Ca elsewhere in the Colorado River Basin to start with. Second the idea of Hoover dam was to prevent a repetition of the 1905 floods which caused the Colorado to flow into the Salton Sea. The efforts it took Hoover to get the states to agree on how to divide the river’s waters up are a tale. Also the public private issue of who should own the powerplant. Hoover dam when built was the tallest dam in the world, as well.

The tale of Ca taking more water than it was authorized since Az was not taking it until the Central Arizona Project was built is interesting, and how 1/2 of the power produced at Hoover Dam is used to pump the water to LA from the Colorado River.Report

Thanks, Burt, this piece just saved me about 10 hours of research and linking for the post I’m working on right now.

Mine’s kinda gloomy, though.Report

Very nice. I love pieces about Western water law and the California Water Wars.Report

How appropriate that LA began with a ditch.Report

I have it on good authority that San Francisco began with a sewer. 😉Report

Actually if you read a bit you find that between Broadway and California Streets in San Francisco, was originally a bay. During the gold rush ships were abandoned there, some actually converted into buildings. Of course back then that part of the bay was essentially a sewer as well as waste just got dumped there. So yes the downtown area of San Francisco. (From the Ferry Building back on the flat lands) was originally water and essentially an odoriferous during and after the gold rush,Report

This was seriously awesome, Burt.Report

Yeah, it’s pretty close to my favorite blog post on the blog, ever. Richly sourced, neat story, some inside baseball, awesome stuff.Report

You’re making me blush.Report

Well, serious awesomeness deserves appropriate acknowledgment, doesn’t it?Report

Ahh, the city of the future.Report

I haven’t read through the comments yet (has anyone brought up Chinatown yet?), and I might have more to say later (though really, what’s to say?), but for now I just wanted to say that this post crushed it — just knocked it out of the park. One of the very best ever I’ve seen here, really.

I’m proud to have it up here, especially since I think Burt could have easily sold it to a larger venue.

Awesome, awesome job.Report

I brought up Chinatown because that is the first thing that comes to my mind when I think about LA and Water.

I spared everyone a quoting of “Fur’f zl fvfgre! Fur’f zl qnhtugre!” [BL: I rot13’d the spoiler on the off chance someone hasn’t seen the movie.]

Until nowReport

“It’s a blister! It’s a slaughter! It’s a blister! It’s a slaughter! …”Report

The movie is from the 1970s. The statute of limitations on spoilers has run out by now.Report

There is a brief allusion to the film (with a link!) subtly included in the OP.Report

Thanks for this, Burt!Report