America Indentured, Part I : What it Really Means to be MADE IN AMERICA

[Note: This is the first in a four part series, in which I hope to start a conversation about the working conditions we allow — or even welcome — when it comes to society’s least important or desirable citizens. Part II will be posted one week from today. Also, please note that while I don’t believe a trigger warning is warranted, there is absolutely some unpleasant subject matter ahead.]

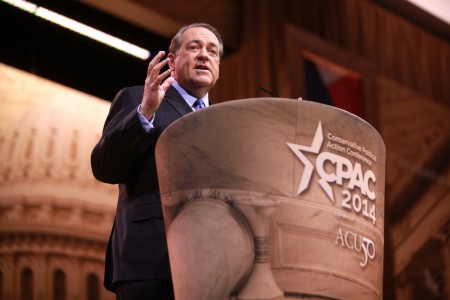

Over the past several weeks, flailing POTUS candidate Mike Huckabee has made minor horse-race headlines by speaking out on the subject of slavery. Not once, but twice.

The first instance came on September 9, when the Southern Baptist minister declared that the court’s holding Rowan County Clerk Kim Davis in contempt was akin to supporting slavery. Speaking on ABC’s This Week, Governor Huckabee suggested that if one believed the Supreme Court’s decision in Obergefell v. Hodges went against the grain of Constitutional authority, that a person had both a legal right and a moral duty to ignore the ruling:

So I go back to my question. Is slavery the law of the land? Should it have been the law of the land because Dred Scott said so? Was that a correct decision? Should the courts have been irrevocably followed on that?

Huckabee’s question, though clothed in the tapestry of historic precedent and legal jurisprudence, is largely a moral one. If the courts rule in favor of a custom as obscene as slavery, he seems to be asking, what is our obligation to follow that ruling? My own personal objections to declaring same-sex marriage the moral equivalent of human bondage aside, Huckabee’s use of Dred Scott should not be all that surprising. In America, after all, there are two historic examples always reached for when one is looking for an over-the-top example of evil: Hitler, and slavery.

Huckabee’s question, though clothed in the tapestry of historic precedent and legal jurisprudence, is largely a moral one. If the courts rule in favor of a custom as obscene as slavery, he seems to be asking, what is our obligation to follow that ruling? My own personal objections to declaring same-sex marriage the moral equivalent of human bondage aside, Huckabee’s use of Dred Scott should not be all that surprising. In America, after all, there are two historic examples always reached for when one is looking for an over-the-top example of evil: Hitler, and slavery.

What was surprising, especially in the context of his earlier comments regarding Davis, was his conversation with conservative radio host Jan Mickelson a few weeks later.

If you do not live in Iowa, it is likely that you are unfamiliar with Jan Mickelson. To say that Jan Mickelson is “just” a local talk show host, however, would be somewhat incomplete. His influence in Iowa Republican politics — and therefore in GOP presidential primaries — is enormous, as the L.A. Times noted in 2007. In February of this year, in a feature story for Bloomberg News, Dave Weigel reported that Mickelson is one of three grassroots gatekeepers “no GOP candidate [hoping for the POTUS nod] can ignore.”

This past August, Mickelson briefly made the national news cycle when he floated the idea of reintroducing slavery as a “common sense” solution to illegal immigration:

Anyone who is in the state of Iowa that who is not here legally and who cannot demonstrate their legal status to the satisfaction of the local and state authorities here in the State of Iowa, [becomes] property of the State of Iowa. So if you are here without our permission, and we have given you two months to leave, and you’re still here, and we find that you’re still here after we we’ve given you the deadline to leave, then you become property of the State of Iowa. And we have a job for you. And we start using compelled labor, the people who are here illegally would therefore be owned by the state and become an asset of the state rather than a liability and we start inventing jobs for them to do.

Mickelson did not initially use the word “slavery” in his proposal. However, when a caller suggested that the proposal would be seen as slavery, Mickelson responded, “Well, what’s wrong with slavery?” Mickelson, who considers himself a Constitutional Originalist, went on to say that the verbiage of the 13th amendment actually allows for the legal practice of both slavery and indentured servitude. [efn_note]This is actually true: According to the 13th Amendment, “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction” [emphasis mine, obviously].

In addition, the Constitution’s protections would not be applied to non-citizens under most strict Originalists’ interpretations, making the question of illegal alien’s criminality somewhat moot anyway.[/efn_note]

In talk radio circles, this is one of those bats**t-crazy, populist ideas that’s picked up what might be described as some minor “but-for” steam: But for the way liberals would paint this as evil, it would be workable. But for the way the liberal mainstream media would demonize us for bringing back slavery to those who deserve it, a “free” labor source of non-citizens could be used as a way to not only solve the immigration problem, but also to reduce both taxes and debt; and so on. Indeed, the caller I noted above — the one who initially called in to take Mickelson to task for promoting slavery — was himself swayed by the radio show host’s argument that by entering the country illegally, South-of-the-border aliens had already expressed a de facto agreement to become property of the state.

In talk radio circles, this is one of those bats**t-crazy, populist ideas that’s picked up what might be described as some minor “but-for” steam: But for the way liberals would paint this as evil, it would be workable. But for the way the liberal mainstream media would demonize us for bringing back slavery to those who deserve it, a “free” labor source of non-citizens could be used as a way to not only solve the immigration problem, but also to reduce both taxes and debt; and so on. Indeed, the caller I noted above — the one who initially called in to take Mickelson to task for promoting slavery — was himself swayed by the radio show host’s argument that by entering the country illegally, South-of-the-border aliens had already expressed a de facto agreement to become property of the state.

By the time Huckabee sat down as a guest on Mickelson’s show two weeks ago, the idea of making people property of the state had been expanded as a solution to the entire criminal justice system. During the interview, Mickelson asked Huckabee if he did not support scrapping the very concept of prisons — a “pagan invention,” dismissed Mickelson — in favor of a Biblical-based criminal justice system that followed the mandate of Exodus 22:3. Under such a system, Mickelson pitched, those with enough money would be allowed to pay their way out of of trouble. As for those with insufficient economic resources to pay court-mandated restitution, he insisted that the state should “take them down and sell them.” When Mickelson asked if such a system wouldn’t be an improvement, Huckabee answered that “it really would be. Sometimes the best way to deal with non-violent criminal behavior is what you just suggested.”

It’s worth stopping for just a moment to zoom out and take stock of these events.

If this is your first time reading about Mickelson’s proposal to have society’s less desirables become property of the state and sold into indentured servitude, or Huckabee’s eye-popping response to this idea, it’s likely your jaw may still be hanging in disbelief. And if you are of the Left, perhaps it is merely confirmation of your assumption that the Right is nuttier than a sack of wet cats.

But to whatever degree all of this approval of slavery and indentured servitude in our modern age seems inconceivable to you, know that it really shouldn’t. For one thing, it’s not the first time we’ve seen a currently well-respected public figure come out in favor of human bondage. As I have argued before, the longer and more overly-winding (or windy) roads you’re willing to let your intellect go down in the service of winning a debate, the greater the chances you end up at a place you’d have previously sworn you’d never, ever go. [efn_note]Seriously.[/efn_note] The human mind, after all, is an often confusing, often contradictory, and often dark thing.

But there’s actually a different, better reason why Mickelson and Huckabee’s opinions on slavery and indentured servitude shouldn’t come as a big surprise.

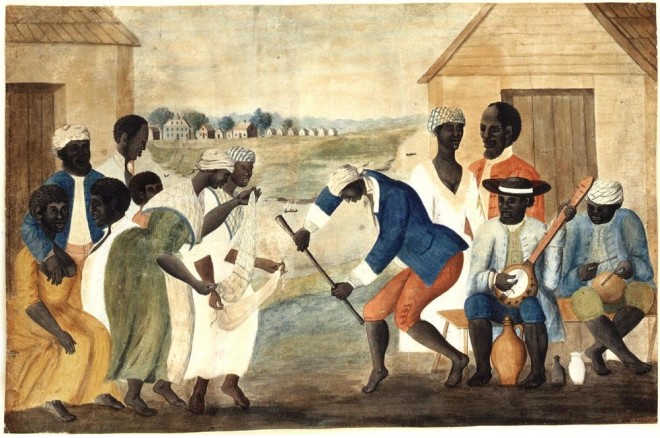

The truth is that what Mickelson proposes isn’t actually all that radical. In fact, to one degree or another, the United States or its citizens have been involved in some form of this type of indentured servitude on a pretty regular basis for at least the past several decades. Similar to Mickelson’s suggestions, the systems usually (but not always) involve non-citizens and criminals. And for the most part, these systems are remarkably visible. They are allowed to continue for surprisingly long periods of time, and rarely are they done underground or hidden by conspiracy. Indeed, they are likely to be well-known to legislators, government regulators, and bureaucrats alike, and also part of the public record. When they are eventually stopped — if they are eventually stopped — there is little if any punishment doled out to the perpetrators.

These systems exist, in other words, not despite our collective wishes so much as because of them.

This four-part series will look in-depth at just a few examples of these modern, publicly approved, and often perfectly legal exploitations of society’s underbelly in the U.S. labor structure. As I will show, Americans and their government are largely satisfied with systems that embrace forced and indentured servitude — often to the point where any arguments that those systems aren’t slavery or indentured servitude are a mere niggling over semantics. Further, I will demonstrate that we as a people largely approve of businesses subverting local, state, and federal employment laws — provided that we find those business’s workers to be sufficiently unimportant or contemptible. Finally, I hope to establish that this is not a Republican problem, a Democrat problem, or even a Libertarian problem. It’s an American problem, with more than enough blame to go around.

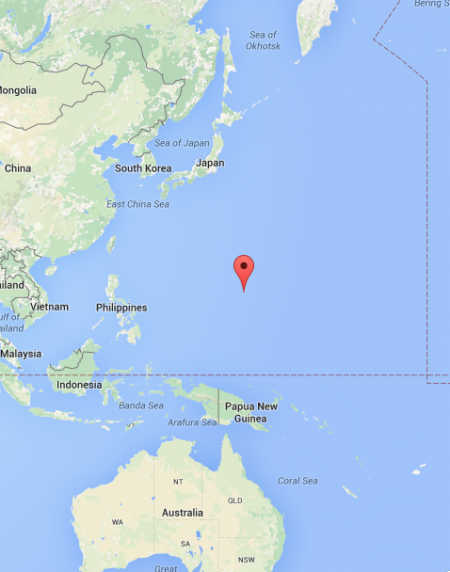

To begin this series, let’s start in that corner of America where hopeful immigrants gather to pursue their dream of American citizenship. That place where those poor and huddled masses, often with families and children still in their country of origin, have traveled to work for a free and better future. That fertile crescent of the American Dream that produces goods that proudly carry the Made In America label:

A tiny group of Pacific islands, nearly 6,000 miles west of California’s coast line and 4,000 miles west of Hawaii’s.

* * *

The Commonwealth of Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI) is, in many ways, the very definition of a tropical paradise.

Situated in-between Japan and New Guinea — its two closest non-trivially sized neighbors — its topography is nothing short of gorgeous. White sands, blue seas, and lush tropical flora make CNMI look like the quintessential dreamscape of where you’d live after you win the lottery. No less an authority than the Guinness Book of World Records has declared its climate the most equitable on the planet. Google its capital island, Saipan, and the search engine will return countless photographs that make Hawaii look like Toledo, Ohio by comparison. Because of this, CNMI is rightly a poplar luxury vacation destination for wealthy Japanese vacationers.

Situated in-between Japan and New Guinea — its two closest non-trivially sized neighbors — its topography is nothing short of gorgeous. White sands, blue seas, and lush tropical flora make CNMI look like the quintessential dreamscape of where you’d live after you win the lottery. No less an authority than the Guinness Book of World Records has declared its climate the most equitable on the planet. Google its capital island, Saipan, and the search engine will return countless photographs that make Hawaii look like Toledo, Ohio by comparison. Because of this, CNMI is rightly a poplar luxury vacation destination for wealthy Japanese vacationers.

Like most beautiful tropical islands with indigenous populations, CNMI spent hundreds of years in the possession of far-off countries after they were “discovered” by the Western world. Spain declared the islands theirs in 1541, and then sold them to Germany in 1899. After World War I, the League of Nations passed them on to Japan. Within two decades, over 50,000 Japanese citizens and military personnel lived there. Almost all of them perished during the United States’ invasion of the islands in 1944. After Japan’s defeat, the islands came under U.S. control, and in 1975 they became an American commonwealth territory. Within a year of that, U.S. legislators and business interests began to construct what many have since called a virtual slave system, what nearly everyone agrees is at the very least indentured servitude, and what a leading member of the US Congress glowingly praised as “a perfect petri dish of capitalism.”

If you bought clothes that were “made in America” between 1988 and 2009, there is a good chance they came from this spot.

The system created by the United States and its corporate citizens is one that can only be described as horrific. And it lasted for decades before it was finally reformed — although to what degree one believes it actually has been reformed continues to be, as we shall see later, something of a matter of faith.

How this system was allowed to fester by both major political parties is an important part of the CNMI story. So too is the current whitewashing of that story — a whitewashing perpetrated by both parties, to create the illusion that the nation’s sins were but the fault of a rogue lobbyist and disgraced Congressman. The reaction of the American public upon being informed about this abhorrent system — a revelation that was revisited and rehashed in the most public of forums regularly over a twenty year period — is perhaps the most important aspect of the story. And we will get to all of that in the second part of this series next week. But before we can fully process the hows and whys of CNMI, and how that system was finally ended (to the degree that it was), it’s important to understand what that CNMI system entailed.

* * *

After its introduction as a United States territory, CNMI was held to special, business-friendly standards in order to promote economic development. Manufacturers that setup shop in CNMI were given a three-legged stool of government non-interference on which to build and conduct business, through various legislation passed between 1976 and 1988. In many ways, this three-legged stool represented the embodiment of the libertarian dream. (Or, perhaps more accurately, the dream of a certain type of libertarian.)

The first leg of the stool was an agreement with the United States that products manufactured on a CNMI island were considered to be made on American soil. So, if you made a widget on Saipan, the capital island of CNMI, it was exempted from all taxes, tariffs, and various customs holdups to which products made in other U.S. territories or foreign countries are subjected. From a legal standpoint, shipping goods from Saipan to Texas is pretty much the same as shipping them from New York to New Jersey. This is why clothing and other goods made in Saipan are allowed to carry the label MADE IN AMERICA. [efn_note]Recently those labels have been changed to read “MADE IN AMERICA (SAIPAN).” [/efn_note]

The second leg of the stool dealt with U.S. employment laws. Manufacturers doing business in CNMI were exempt from quite a lot of them. This included various U.S. wage laws, including the federal minimum wage, employee safety regulations, and government oversight. And as was discovered multiple times in the 1990s and 2000s, those wage and safety laws and regulations that companies were required to follow were rarely enforced. In fact, CNMI factories could have local judges bar government auditors and health and safety inspectors from entering factory grounds.

The last leg to the stool was this: CNMI was exempt from almost all U.S. immigration laws. This meant that although CNMI citizens were considered to be U.S. citizens and were thus granted basic Constitutional rights, corporations doing business could bring any number of workers from foreign countries that had no rights whatsoever. And they could do so without permission from or notification to the government. Further, a foreign worker’s status regarding both entry to the country and deportation was determined not by the U.S. or CNMI governments, but by the corporations that hired them.

Here is the result of this three-legged stool: [efn_note]There’s a lot of claims of very specific facts here, but please don’t think I’m just making this stuff up. Here is a list of source material I used while preparing this piece, where you can find everything referred to herein, and more.[/efn_note]

Workers were brought in by the ship-load, primarily from China, the Philippines, and other Asian and Pacific Island countries. All of these workers had signed contracts. However, the third-party headhunters employed to sign up workers tended to target illiterate women, usually with little more than a first grade education. The contracts, manufacturers, and headhunters all varied, of course, and thus so too did different contract specifics. However, there were some troubling patterns that quickly emerged.

Many women were told that by headhunters that these contracts were the first step in a fast-tracked process toward moving their families to the United States; some were even promised eventual citizenship status. They were often promised wages far greater than they would actually be paid. They were promised access to enough funds that they would be able to send back money on a regular basis to support their families until such time as the families could join them. In fact, largely because of this last bit, many who signed on had children they left behind with relatives, on the assumption that the children would soon follow. Many of the women were told that they were coming to the islands to be part of its tourism industry; most of these arrived with the understanding that they were going to be waiting tables and changing beds at posh resorts. In fact, almost all of them had been brought to CNMI to work at garment factories.

What is perhaps more important, however, is the parts of the contracts that were not shared with the women.

Workers agreed to work any amount of hours requested by their employers. Usually, this resulted in six-day, 10-14 hour work weeks; overtime was not paid. Workers going to CNMI also agreed to borrow money for the expenses needed to travel to the islands. These amounts were often grossly inflated considering they were usually taken on what were basically cargo ships. Some (more extreme) contracts listed this travel expense as high as $12,000 US. dollars; the interest on these loans could go as high as 20%. Most of the wages they earned — often just a few dollars an hour, if they were paid (many were not) — went first to pay these travel fees, meaning that workers often had to labor for years before they were free from debt.

Workers agreed to work any amount of hours requested by their employers. Usually, this resulted in six-day, 10-14 hour work weeks; overtime was not paid. Workers going to CNMI also agreed to borrow money for the expenses needed to travel to the islands. These amounts were often grossly inflated considering they were usually taken on what were basically cargo ships. Some (more extreme) contracts listed this travel expense as high as $12,000 US. dollars; the interest on these loans could go as high as 20%. Most of the wages they earned — often just a few dollars an hour, if they were paid (many were not) — went first to pay these travel fees, meaning that workers often had to labor for years before they were free from debt.

Further, the workers agreed to waive any and all legal (and, some might say, human) rights that might otherwise be granted them. In practice, this often included the right to leave the factory compound during off hours, to attend or practice religious observances, and the right to socialize with others of their choosing.

Employers could terminate a worker at any time for any reason, and if they did so they were allowed to take the employee wages they were holding to pay for whatever expenses the employer saw fit to collect. Employers also regularly held all passports, legal papers, and any form of personal identification that the employees needed to return home.

Under these contractual conditions, the employee-employer environment developed the way you might expect, only worse.

Compounds were built to “house” employees when they were not working. These compounds often lacked basic furniture, and over the years ex-employees and human rights groups would testify before Congress that many were built without access to electricity, plumbing, or potable water. As many as twelve women would be housed in tiny, windowless rooms. In many factories, employees were not allowed to leave the compound, even when they were not working. To ensure this, these compounds were guarded both by barbed wire and private armed guards.

Physical and sexual assault were not uncommon. Worse, employers with a downturn in orders sometimes forced the women to earn money as prostitutes for the island’s tourists. Although the women were not given any form of birth control, all employment contracts strictly forbid pregnancies. If a worker did conceive, the company would have in-house staff abort the child, regardless of the employee’s wishes.

Physical and sexual assault were not uncommon. Worse, employers with a downturn in orders sometimes forced the women to earn money as prostitutes for the island’s tourists. Although the women were not given any form of birth control, all employment contracts strictly forbid pregnancies. If a worker did conceive, the company would have in-house staff abort the child, regardless of the employee’s wishes.

For those employees who contracted with the worst offending employers, there were only two options: The first, obviously, was to live as indentured servants until, after a sufficient amount of months or years, the company decided that a fresher body would do more work and shipped them back to their country of origin. The other was to try to escape and go home, but this was not as wise an option as one might first guess. For one thing, their passports and papers were usually held by their employers, as often times was their money. Even if a worker was able to slip past the guard and get through the barbed wire, there was nowhere for them to escape to — or at least nowhere that was enviable. Those women who did escape, as well as those terminated without pay, found that other companies on the island would not hire them. More often then not they ended up homeless, selling the only asset they still had available to them: their bodies.

* * *

I first became aware of the situation in CNMI in 1991, after Levi Strauss came under scrutiny for the conditions of their contracted manufacturers. Then, as now, the predisposition of Americans to turn every conversation about government policy into a political debate meant that everyone who discussed it — in Congress, on NPR, at my neighborhood bar — fixated on one question above all others:

Yeah, but since there’s a contract and it’s only temporary, is it really slavery?

What a stupid, useless, and short-sighted question that was then, and remains today.

Over the decade and a half that followed, up until the time a Washington, DC scandal gave everyone an out from having to face their own complicity, that’s what discussions about CNMI inevitably wrought. Not an outraged call for action, but a vapid quibble over semantics. How easily we human beings can un-see ongoing horrors, when it is in our interest to do so.

And that’s why Jan Mickelson’s idea, currently sifting through the talk-radio circuit as we speak, isn’t some crackpot, lunatic rant that could never happen. Of course it could happen. It could happen pretty easily. After all, what Mickelson proposes isn’t really that different from what we just did to hundreds of thousands of Asian women for decades. For that matter, it isn’t all that different from what we let people do to undocumented workers in this country today.

And that’s why Jan Mickelson’s idea, currently sifting through the talk-radio circuit as we speak, isn’t some crackpot, lunatic rant that could never happen. Of course it could happen. It could happen pretty easily. After all, what Mickelson proposes isn’t really that different from what we just did to hundreds of thousands of Asian women for decades. For that matter, it isn’t all that different from what we let people do to undocumented workers in this country today.

We wouldn’t call it slavery or even indentured servitude, obviously, and we certainly wouldn’t refer to “them” as property. Those are all words that would shine too bright a light on our public policy. Instead, we’d do what we always do: find euphemisms that allow us to take full advantage of cheap labor without having to face the reality of what it was we were collectively allowing.

It’s a thing to keep in mind, as the debate over what to do with undocumented workers heats up in the coming years.

[Next up: A look at how the U.S. political system, media, and public dealt with the Mariana issue over time, and collectively chose to allow it to continue unabated.]

[Images: Slave Dance with Banjo, folk art via Wikipedia; Northern Mariana, via Wikimedia; Mike Huckabee via Wikipedia; Jan Mickelson screenshot from YouTube, Immigration Day protester via Wiki Commons, Garment workers via Wiki Commons.]

Erik Loomis at LGM speaks about this issue a lot since it is in his bailiwick. Many people in the United States and elsewhere want to live affluently and they want to live it cheap. The only to combine these two contradictory forms of thought is through an extraordinarily cheap labor source. Since perfect automation is not possible, this means indentured labor or slave labor. As Loomis notes, one way to do this is to make sure these things occur out of sight. During the Gilded Age, many affluent Americans grew to point where they could no longer ignore the abuses occurring in factories and began to campaign against child labor or other sins of the system. Putting slave labor in a place like CNMI or using undocumented aliens, prisoners, and other undesirables as pseudo-slaves is a way to avoid this problem.

Loomis’ proposed solution is to make labor as mobile as capital, or what others would call the borderless world, because he believes that this would allow for labor cooperation and coordination on a global level and eventually global labor standards. He also thinks that the United States and other developed nations should impose first world labor standards on developing nations. Both proposed solutions have serious problems. While the idea that countries should be nothing more than administrative units like counties is popular among some progressives and libertarians, most people do not really want a borderless world. To them nations still have cultural identities that are important to them and they also tend to be cynical about international government. The problem with the second solution is that nobody really wants to do this either and there is no real effective way to enforce standards except a simple bar on imports from countries whose labor laws don’t meet developed world standards.

Lee already brought up the Loomis Out of Sight theory. Americans (and probably people all over the world) want to live well and cheaply. The way you do this is through making sure that human rights abuses occur out of sight. These islands are a perfect example. Extretmely remote with a plausible deniability that it is and is not U.S. soil. Rural prisons and out sourced factories are other examples.

For the broader point, I’ve noticed that the right-wing in general uses Dred Scot as a code word for any Supreme Court decision that they dislike from Roe to SSM. In general, I’ve noticed that a good chunk of Americans are rather authoritarian and/or subserviant to authority despite constantly talking about how America is great because of freedom and freedom. You can see this whenever there is a story about police abusing their power. A good chunk of this country seems to think that the police can do no wrong.

While consumer complicity is undoubtedly a factor, I struggle to accep that the bulk of the responsibility does not lie with the corporations or the lawmakers who empowered them. While @leeesq is right that the desire for affordable affluence exists, we also know that the cost of production does not dictate sale price. True Religion jeans don’t cost $200 because they cost $150 to make and sell. They cost $200 because that is what people are willing to pay for them. And TR will sell them flr that price whether the cost of production and sale is $15 or $150. Because if they can sell them for $200, they will. And if they can exploit the system to make them for $15, they will and will line the pockets of the higher ups and those they need to buy to make it happen.

So, yes, consumers wanting cheap jeans or lettuce or iPhones who are willing to turn a blind eye to the problem contribute. But primary blame lies with those who creat and maintain the system and do so to grow their own personal wealth: company executives/directors and legislators. Especially when they go to great pains to keeping consumers blinded to the reality of what is going on.

This isn’t meant to absolve anyone of responsibility and I agree that the “But contracts!” retort is disgusting. But we can shake our finger at a naive public without losing sight of who actually enslaved and abused these poor people.

This is the shit that makes me think wage caps and/or price controls might not be such a bad idea.

Damn comment eating. Price Controls are not going to work. If you can only charge 50 dollars for a pair of jeans, all jeans are going to cost around 50 dollars. This will hurt the poor and middle class and benefit the rich. Likewise, maximum wage laws will only work if you find ways to gut the savings and investments of the rich and make sure people don’t hide their money and/or get paid in equity and perks. IIRC when Roy Cohn was in private practice, he was only paid a dollar a year by his firm but the firm also paid for his housing, food, and all other expenses.

kazzy,

I don’t follow your last sentence. Wouldn’t wage caps make things worse for workers (because the employer would be forbidden to pay them more)?

And how would price controls work? If they were, say, fixed at a certain rate over cost I suppose that might take away one incentive to treat workers harshly. But it would be really hard to enforce, and could encourage cartelizing industries. That’s partly what was attempted under the National Recovery Act during the New Deal, and it didn’t seem to work. (However, to be fair, the federal government’s commitment to the plan was pretty weak and it was introduced only as an “emergency”–which many interpreted as “temporary”–measure.)

Wage caps at the top. No CEO needs to earn 9 figures. But if needlessly chasing that number leads to this behavior, it’s a problem.

Thanks for clarifying, Kazzy.

@gabriel-conroy

And I should further clarify that I don’t necessarily believe in wage caps or price control… but if anything could get me behind it, it would be the enslavement of people so that folks can earn 9 figures instead of 8. Ugh.

We’ve been over this before but the CEO of the company I work for could cut his wages to zero dollars a year, distribute the result among the rest of the employees, and the result would be a 2% increase in pre-tax wages. Not exactly a revolution in the social order, that.

Business people are going to what is best for their bottom line for the most and there are always going to governments that allow them to do so for a variety of reasons ranging from true belief in capitalism to something more venal. In order to get a better situation, people need to advocate for change. Workers must organize and strike and middle class people have to join them rather than turn a blind eye.

I think more people need to be aware of the difference between costs of various pieces of production and market price. When people give us grave warnings for $15 heads of cabbage if we pay cabbage pickers more, I can only wonder how much of the cabbage’s price is the few seconds a human spends picking it up off the ground versus all of the other stuff in the pipeline.

That $28 tee shirt isn’t $28 because we were just barely able to keep the lady in Saipan from demanding $29 to make it. It’s $28 because we paid the lady in Saipan a few cents, paid the cotton suppliers $X, paid the shipping people $Y, the retailers $Z, the shareholders $S, etc. I’d have to guess that paying the lowest paid sweat shop workers twice as much per hour simply wouldn’t affect retail prices very much for most goods.

That’s my point. We here if we increase cost X, then prices will rise. But that assumes that other things can’t yield. They can. But the powers that be aren’t willing to let them and we wrongly accept that. You could double the lowest wage earners salary AND cut prices AND still profit. But they won’t because that money would have to come from someone and it sure as hell won’t be the CEOs pay.

I remember when talk of living wages for fast food walkers led opponents to claim that a Big Mac would cost $15. Regardless of how you feel about living wages/minimum wages, there is simply no math in the world that supports that form of opposition.

Exactly. I don’t know what the breakdown of the costs of a Big Mac are, but I’d have to guess that rent on the building and equipment, licensing the McDonald’s name, and the purchase, shipping and storage of input ingredients make up most of it. The whole point of “fast food” is that labor touch time is minimized by clever engineering and simplification of the food preparation process.

I’m trying to remember some of the numbers people cited during the labor symposium a few years ago, and what types of businesses those numbers applied to, but I recall one number bandied about: that labor (which doesn’t include management’s salaries) constituted something like 6% of total costs. If that’s a baseline, then increasing labor compensation by 50% would increase total costs by about 3%. So the price of a $2.00 burger would have go up to $2.06 to make the same profit. Something like that. (Did I do that right?)

For all sectors it’s *60* percent, not 6.

http://www.bls.gov/lpc/faqs.htm#P04

“In the US non farm business sector, labor cost represents more than sixty percent of output produced.”

https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/magazine/whos-lovin-it/2011/08/12/gIQAoOVRuJ_story.html

Who is the most spectacularly underpaid in the McD’sverse (aside, I suppose from the cows), are the franchise location managers if that article is any indication. Profiled is a man with complete responsibility for about a 100 people and 24/7 operations and seems damn good at his job, but is pulling down about 40k per year. Other companies have tried to lure him away offering more money, but he’s scared his nearly non existent written English ability will cause him to fail at another position (and he’s probably right)

I found some numbers from Heritage which put labor and payroll-taxes at 26% of sales for a typical fast food restaurant, but it appears they’re lumping salaries in with hourly wages. I don’t know what the breakdown of for each would be, but obvs hourly labor would account for less than 26%. So, say 20%? (Probably upwards of that.) So a 50% raise in labor costs translates to a just under a 10% increase in price to retain profits all things being equal. $2.00 burger goes to $2.20-2.25.

Here’s the Heritage info.

To be clear, my argument isn’t that increasing wages will have NO effect. My argument is that it won’t have the effect most opponents claim. More importantly, the reason it would have that effect is because of the misguided notion that existing profits must be maintained or increased. Why couldn’t McD’s* pay the increased wages and accept profit of $500M instead of $1B? Why would that be such an awful thing?

* I know McD’s isn’t the best example because it is largely franchises but it is what we are working with. Still, the issue holds that the top will never feel the pain unless or until the company goes under, and even then they tend to protect themselves. I even see this in schools. “Enrollment is down. Fire the teachers or freeze their salaries. Oh, but admin won’t shrink and we’ll continue to take our raises.”

@kazzy

More importantly, the reason it would have that effect is because of the misguided notion that existing profits must be maintained or increased.

Misguided? Not at all. Let’s look at this a few different ways:

McDonald’s common stock: A share price is priced at a certain point based on a number of different factors including 1) projected future cash flows (profits) and 2) those cash flows being discounted at a risk-adjusted rate (the cost of equity capital).

Using your example, on a purely mathematical basis, a 50% reduction in profits would lead to a 50% reduction in the share price unless the corresponding discount rate (cost of capital) lowered enough to offset the decrease in profits. That won’t happen. A reduction in the risk-adjusted rate of return implies a reduction in risk; however, if the company thinks it’s not such a big deal to absorb labor costs and show a complete disregard to shareholder interests, investor faith in the ability to make money will likely shrink making McDonald’s a more risky investment thereby INCREASING the discount rate. Perhaps the share price decreases by even more 50%.

Investors that will have lost their asses on McDonald’s will sell out.

McDonald’s bonds: This one is arguably worse because. I explained the risk perspective above, but there’s also a credit perspective. Allowing what you suggest to take place would significantly impact McDonald’s performance and operating metrics. If the change is significant enough, the ratings agencies are going to jump all over it and downgrade McDonald’s both as an issuer and any existing bonds outstanding. While the outstanding bonds may not be in a position where a default is imminent, any investor forced to sell them to maturity will take significant losses.

A potentially bigger problem…

Future capital needs: Given the company’s revised risk and credit profiles, in the event the company needs to access the capital markets (and it will at some point), with a lower credit rating, it’s cost of borrowing is now higher (higher interest costs reduce profits). On the equity side, you have a company that has a bad story, lower profits and weaker margins that competitors. If companies like YUM Brands or other publicly-traded fast food companies have better metrics, investors will rather invest in those unless they are compensated for taking on additional risk, compensation that is translated to more expensive equity and less capital raised through the equity markets.

This is the shortest answer I can give. Although it’s not as good as I’d like it to be, the key takeaway here is that before anyone asks “can X company afford a hit to profits?”, look to the capital side of the equation before you answer. When you do, you’ll see why the notion you said was misguided isn’t misguided at all. It’s not just the people at the top. It’s the entire capital structure that’s in play.

The $15 minimum wage has cost Seattle 1300 jobs yet liberals are still pushing it.

http://www.economicpolicyjournal.com/2015/08/seattle-has-lost-1300-restaurant-jobs.html

According to a linky in your linky:

Seattle et al lost 2100 jobs from Jan-May (the min wage hike went into effect in Jan), then added 2100 jobs from Jun-Aug. Now it’s dipping again….

@troublesome-frog

You’ll find that labour is a large part of the cost of most goods. Certainly not all, but especially for commodity products like cabbage labour will be a lot of the cost.

That’s labor in general though, not necessarily one specific component of labor. The tension with wages for produce, for example, always seems to be about getting enough temporary workers to handle just the harvest. “We’ll have to let the produce rot because we can’t find enough people to harvest it!” is the refrain.

Given everything that goes into an entire growing season and the amount of time a picker spends on a single head of cabbage, that component seems like it’s unlikely to produce anything along the lines of $20 heads of cabbage. The quick bit of googling I could do gives $6 per ton of cabbage ($0.003 per pound) as the piece rate paid to harvest laborers.

Likewise, I’m sure labor is a noticeable piece of that $28 tee shirt. The labor of the slave woman who sewed it, not so much.

The problem with farmers (and a lot of these cheap commodity good producers) making ends meet seems to be less with the cost of any given input and more with the fact that they’re in a really competitive market, so wholesale margins are terribly thin and everybody has to do whatever they can to keep costs down. People confuse the impact of a wage increase on one employer in a competitive market with the impact of a wage increase that hits every employer equally.

At the risk of getting into the semantics, I have a hard time calling the situation you describe anything other than slavery. For me, the important thing is there’s no meaningful option to quit.

Do orphanages then count as slavery, if they come with a work-requirement?

Without knowing more, I’d say yes. Orphanage residents are children, and children don’t really have the legal right to dictate who they live with and under what terms. Adding a work requirement in “exchange” for something they didn’t choose sounds pretty sketchy. I suppose it depends on whether the work requirement is along the lines of, “clean the living space,” or, “make garments for us to sell and keep the profits.”

If the purpose is to contribute to the household that takes care of you, that’s one thing. You’re arguably enjoying the profits of your labor. If the purpose is to make money for somebody else, that’s quite another.

I should think so. Child slavery, to boot.

Can you show documentation of such institutions?

zic donates to an orphanage who does this.

A friend of mine “inherited” an orphanage that does glasswork. I can provide you the links to the glasswork if you’d like to purchase some.

These are South of the Border, where I understand things are considerably less strict about youth workers… So, yes, this may actually be quite legal.

This is an article about actually problematic conditions:

http://www.ipsnews.net/2014/08/mexicos-orphanages-black-holes-for-children/

I’ll maintain that slavery’s hardly the worst thing one can do to a child. (though, quite frankly, it’s far from the best either.)

Interestingly two anecdotes,

I had brunch on Saturday with two people who work or worked at a big and famous consulting company. They both said that the employees who work the hardest in their big and famous consulting company are ones who are located in countries like Spain and Italy because those countries have relaxed working cultures and it is hard to get productivity. Employees in the U.S. and Northern Europe work hard but are less stressed.

On Sunday, I was talking with an Italian woman who won the green card lottery. She likes it in the U.S. but was shocked by what employers could get away with in terms of how employees were treated.

Make of this what you will.

Who works hardest and why, again? I’m having trouble making the parts of these two sentences line up.

A couple of misc. points, mainly because I’m a bit pedantic.

Schematics ARE important. Indentured servitude IS different from slavery, if only from a technical or legal perspective. That does not, however, change the situation if the end result is essentially the same, and I’d agree that the workers described on Saipan in this article are effectively living as slaves, particularly given the whole “work as a prostitute and we’ll abort your child if you get preggers” issue. Any of this remind anyone else of the whole “third world sweatshop” stuff the US has been dealing with the for past few decades?

I’m going to agree with Kazzy on the allocation of responsibility, unless someone can demonstrate for me how I am specifically and directly responsible. (Yes, I like super nice stuff super cheap, but I’m not seeing how my desire for an Audi R8 for 30K, which isn’t even possible, is to blame.) No, it’s the corporations and the enabling politicians that have blood on their hands. As to the American public, in general, well, we currently don’t care that our military/gov’t is drone bombing civilians in the middle east, so why should they care about this, other than a minor amount of outrage after listening to NPR and maybe sending a letter to their congress critter? It’s all happening “over there” and doesn’t impact them, and the news cycle moves on to another outrage….

I’m not really familiar with Saipan and this history so it comes as a bit of a surprise. I’m looking forward to you solutions in upcoming posts Tod

“…in favor of a Biblical-based criminal justice system that followed the mandate of Exodus 22:3. Under such a system, Mickelson pitched, those with enough money would be allowed to pay their way out of of trouble.”

Ah, Christian values.

Make America Great Again!

Oddly enough, just down the page is Exodus 22:21

Well, God couldn’t possibly have meant Mexicans as well.

You were never a foreigner in Mexico.

Since this from Exodus, this is a Jewish value and not a Christian value. A Christian could say with a semi-straight face that “for you were strangers in the Egypt”, stranger is the preferred Jewish translation, clearly refers to the Jews because it referring to our experience as slavery in Egypt. Therefore, Christians do not have to obey because their ancestors did not go through the ordeal of Egyptian bondage.

The Torah also explicitly states that denying laborers their wages is akin to theft and fraud among other things.

But the Torah was never against slavery.

(although it did have that whole Jubilee year, which wrecked havoc on the economy).

The Torah did allow for slavery but heavily regulated it as an institution, I realize that this isn’t a great defense, compared to other slavery systems at the time. Under Roman slavery, masters were allowed to do what they will with slaves and they slaves had no choice but to obey. The infamous seen in Spartacus about oysters and snails represented a big reality of Roman slavery. Slaves had to be sexually available to their masters no matter what. The Torah did not allow this.

Modern people look back at all the ancient law codes like the Torah, Draco’s law code of Athens, or the Roman Twelve Tablets as unduly harsh. By modern standards they are but what people do not realize is that the ancient law codes simply put oral customary law into writing. Once something is in writing, you can study it and reflect upon, and talk about it and realize that it is unduly harsh. This leads to reform sometimes.

Desert codes tended to be overly harsh, in part because prison was nonsensical because they couldn’t afford it. (of course, cutting off a hand was nearly a death sentence).

Slavery as an institution can be roughly rated in two directions:

1) What happens to the children? Do they integrate into the tribe eventually? Is there a way out of slavery, or is it in perpetuity?

2) How many slaves per slaveowner? It’s a lot harder to mistreat your only slave… and they’re more likely to be part of the family.

What was that Catholic practice of buying out your sins?

Indulgences.

Thank you! I kept thinking it was Jubilee’s, but I don’t think the disco pop party mutant has anything to do with that.

Horrifying my Tod.

The NY times is running a big series on binding arbitration. Today’s article was on how binding arbitration allows people to impose biblical law on customers and employees.

The big problem is that Christians don’t seem to know how Jewish law worked in practice

That was my thought. Jews interpret the laws of the Torah through the lens of the Talmud and thousands of years of argument and debate. It is not given a literal meaning. My advice is that if an employee finds him or herself in such a situation, their best bet is to hire an Orthodox Jewish lawyer to represent them. That lawyer would have a lot of the necessary knowledge about the Torah or at least know where to turn to get the knowledge.

I can see a lot of lawyers from Borough Park finding this proposition a good idea.

More seriously, bellow is a link that does a good job of showing how the Talmud treats some of the harsher seeming laws in the Torah into something much more modern and humane. It deals how the Rabbis who wrote the Talmud actually abolished away the Torah proscribed ritual of the “waters of bitterness”, an ordeal that was supposed to check if a woman committed adultery or not.

http://www.tabletmag.com/jewish-life-and-religion/194673/daf-yomi-146

I know that digging into the logic of something this far into the fever swamp is a sanity-risking mistake, but I’m kind of fascinated by the internal logic of putting immigrants into indentured servitude. The chief arguments I hear against mass immigration is that it reduces the wages of US workers and that it degrades social cohesion in various ways (crime, language differences, etc.). But as far as I can tell, keeping immigrants here and forcing them to work for free will make these problems worse; they’ll still be in the country speaking spanish and potentially committing crimes, and they’ll be working for free instead of cheap. So what’s the motivation for this, then? Pure animus and spite? Is there some even vaguely defensible justification for this craziness that I’m missing?

Yeah, this is beyond batshiat loony, I mean I hate thinking of government power expanding, and this concept puts more bodies(assets) under government management.

I think the real goal is the same as self-deportation. Make the conditions so unbearable that immigration stops.

Makes sense. I suppose “they will enslave you” is a pretty good reason not to try to immigrate to a place.

Depends on the form of slavery, and where you’re coming from.

Sometimes, I hate the world as we live it.

What really annoys me about Romney’s self-deportation line is that the United States already has a system of self-deportation built into the INA called voluntary departure.

“I think the real goal is the same as self-deportation. Make the conditions so unbearable that immigration stops.”

I thought you lot were strongly in favor of Pigouvian taxes.

If we must save the children, I’d rather we do it south of the border. Its cheaper that way, and one never did anything wrong by putting a child in an orphanage rather than a “detention center”

Pure animus and spite?

Dude, desperate times call for desperate measures, ya know? If enacted, the backers of these policies would lament how they will never be able to forgive those sneaky illegals for making us enslave them, and what a heavy burden that is to bear. They’d be the REAL victims here.

Huh. I had not been informed of these things.

This is NOT to bite at Tod’s ankles, but the description of Saipan as “a poplar luxury vacation destination for wealthy Japanese vacationers” pinged my antennae for a couple of reasons. Firstly, you hardly have to be affluent to go there on vacation from Japan, and indeed given its history, Japanese vacationers aren’t always sure whether Saipan counts as a foreign country. Secondly, poplar is a kind of tree.

Yeah, in the pedantic nitpick department, wealthy Japanese go to Hawaii, middle class Japanese, (and now, perhaps even more Chinese) go to Guam and Saipan.

(and even more nitpicking, what is now CNMI ‘came under the control of the US’ only in the sense that the US was an administrator for a Trust Territory under de jure control of the UN. The interesting thing from a government corruption standpoint is that before becoming CNMI, it tried to merge with Guam as a political entity but Guam rejected it. Had that happened, the peculiar circumstances around CNMI economic regulations would be significantly different)

“(Or, perhaps more accurately, the dream of a certain type of libertarian.)”

Who are we talkin’ about here?

It is kind of interesting that the “a certain type of libertarian” comment is followed immediately by a paragraph on tariffs and protectionism.

If there is one thing I’ve learned about OT, is just because the dots are close doesn’t mean……

Maybe just a hint wink at one of these libertarian types:

1.pro-state

2.pro-state & pro-corporate

3.anti-state & pro-corporate

4.anti-stateX & pro-stateY & pro-corporate

The sketchy part is 2. 3. and 4.

@joe-sal @chris I understand where each of you is coming from, and I’m going to hold off answering too completely because a lot of what I would say is in next week’s installment. And even then, I suspect we will agree to disagree.

That being said, for now I will simply say that in general, I think CNMI appeals to the kind of libertarian who would find a country with no import/export tariffs or taxes, open borders where immigrants and foreign workers are not tracked by the government, no real employment laws, and which had made a decision not to have its government have an office of Attorney General on the logic that if CNMI’s business interests were doing things that were so-called unethical, immoral, or illegal, it should be up to the market to punish them, not the government a good thing.

And more specifically, the kind of libertarians that might write for Reason magazine, who were staunch supporters of CNMI’s system. (Although in fairness and full disclosure, I should note that it later turned out that one of those writers was paid by the lobbying firm Preston Gates to say that it CNMI awesome.)

[Note/Update: The pay-off I noted in the last sentence of this comment was not for a Reason writer, it was for a CATO writer. My bad. CATO being CATO, though, my point still stands.]

It’s seems to me that you’re pulling a bit of a swindle here. The problem wasn’t “deregulation” or “free trade,” but the fact that people were brought to the island through outright fraud. Fraud is put in the same category as force in most libertarian thought, and I guarantee you the writers at Reason did not then and do not now support or approve of a system in which laws against fraud are not vigorously enforced.

If I invite someone to my house for dinner and then kill and cook him, that’s not an argument that our dinner party system is dangerously underregulated. Crime is a problem is all socioeconomic systems.

And is that your only objection here?

In other words, if we could show that the women did in fact understand the contracts, everything in CNMI would be cool?

I joined the military. Pretty stiff terms on those contracts, and the living conditions can be harsh.

@oscar-gordon

The military does not have a real contract system. It has an adhesion contract at best. No rational person would conclude that allowing one party to extend the service duration “for the foreseeable future” with no recourse. Since we’re in the mode to talking about involuntary servitude and slavery, I’d classify someone who’s service involuntary extended as equal to a slave.

Stop loss folks say ‘ORLY?’

Like I said, or said poorly. A “contract” giving all the benefits to one party and imposing all the costs, like stop / loss, isn’t really a contract where two equal parties negotiate terms and come to an agreement. At best it’s an adhesion contract or slavery.

Frankly, I’d call it slavery.

And yet it is a contract that is not only considered perfectly legal, signing it & adhering closely to it’s terms is considered an honorable thing.

Which was my point. If the workers on CNMI were literate & understood clearly what the actual terms of the contract were, then yes, it should be enforceable.

Why does privity of contract rank so highly in your moral universe?

“And yet it is a contract that is not only considered perfectly legal,”

Yah, the organization that write the contracts is also responsible for interpreting it, enforcing it, and unilaterally changing the terms. I’m sure you 100% ok with the adhesion contracts that verizion and comcast, etc. have and that bind you, right?

@damon

We have some drift going on here. I was responding to Chip about his comment on the contract terms being understood.

If the terms are understood & still agreed to, then the contract is valid, even if it offends us.

What violates the contract is the fraud involved in selling the contract. What invalidates the system was a complete lack of any kind of impartial contract enforcement.

As for Adhesion contracts, no, I’m not OK with those, but I recognize that they are legal, if offensive. I also avoid them as much as possible & agitate for changes toward their usage.

Slavery? Yet folks sign up all the time b/c the benefits are good. Sure, just like slavery.

So obviously all these foreign women who were imported to Saipan and especially the ones who became prostitutes when they lost their job, and we’re not allowed to leave the compound, that’s not slavery either right? You’re totally cool with that right?

No. the US military contract is JUST like an adhesion contract. Once you sign up, the gov’t can move the goalposts if they choose. That’s not the definition of a contract. Whether people judge they won’t get hosed by stop/loss or gamble they won’t be sent to combat isn’t the point.

I’m responding to your silly view of the military contracts. In a national emergency the military can’t risk losing qualified folks, so I think the stop loss provision are justified.

Yes, we have had SO many national emergencies….

You’re not really calling Iraq and Afghanistan national emergencies are you? They were / are wars of choice. I could see an argument in WW2.

@notme

Explain that just a little bit more.

On a case by case basis, if the person has truly unique skills, I can see the value in using stop loss in order to retain that person long enough for them to train up a new cohort.

But using stop loss as a tool to offset drops in recruitment because the war in unpopular is:

A) HORRIBLE for morale.*

B) A sure fire way to make sure that your recruitment numbers drop even further as word gets out.

The inability to recruit volunteers for the military is supposed to function as one of the signals to politicians that it’s time to execute that exit strategy. Like now!

If you want a happy army, you make sure your troops have the 4 M’s: Meals, Mail, Money, Morale. Part of that Morale is knowing that at some known point in the future you get to say “60 days & a wake up”.

Yes but sometimes you need troops and you don’t have time to recruit or train them. You don’t just waive a wand and create a infantryman.

I know, I was in the military, remember. But retention & recruitment numbers don’t just fall off a cliff. You see that trend happening from a ways off. The pentagon knew it was facing a crisis years before the crisis hit. It told POTUS & congress the crisis was coming years before it happened. That was the signal to POTUS & congress that it was time to pack up & come home, or to radically change the strategy such that troops weren’t burning out.

Their response was Stop Loss & to keep on keeping on. Which helped retention numbers, but once word got out, caused those recruitment numbers to fall even faster.

The response was stop loss, increased bonuses and lowering the retention standards. It was a combination of things.

So, Libertarianism cannot fail, it can only be failed?

Look, I get that not all (and honestly, most) libertarians would have been in favor of CNMI’s system back when it was running, and I certainly can’t think of any that would come out in favor of it now. But in politics, even politics on an on-paper and academic level, ya gots to own what da peoples do with your framework.

Communists can argue all they want about how all the real-life communist countries weren’t “real” communists like they envisioned on paper, but in the end that’s a fairly meaningless objection to me. In the same vein, CNMI’s system was one that was pitched as a libertarian/free market ideal, was defended/encouraged by free-marketers/libertarians, and was allowed to continue long after it should have been shut down because of free-market/libertarian arguments.

Do all of those people today admit it wasn’t so great, so free market, and so libertarian in an on-paper ideal kind of way? I assume so. But I am a firm believer that one’s ideology has to own its errors, or (if you will) the errors it happily let occur in its name. Otherwise, you’re no different from the crank I wrote about last year who argues that slavery could have worked if only people had done it the way they were supposed to, or the guys who write for the Communist Party USA’s newspapers.

@tod-kelly

So, Libertarianism cannot fail, it can only be failed?

Like CrossFit, and the dogmatic types in both are unbearably painful to deal with.

At least they don’t deliberately leak.

“The cures for the evils of the free market is more free market.”

I’m happy to own the failures of the ideology, but that wasn’t @brandon-berg point.

His point was that there was a great deal of fraud going on, and most libertarian ideology recognizes the role in government for policing & enforcing laws against fraud.

@oscar-gordon I’m happy to own the failures of the ideology, but… there was a great deal of fraud going on, and most libertarian ideology recognizes the role in government for policing & enforcing laws against fraud.

Well, yeah. But that’s the rub, isn’t it? How you want everyone to behave under your political philosophy and how everyone actually behaves aren’t always the same thing. No one wrote in the legislation that set up CNMI’s system, “third parties will be allowed to go out and hire illiterate third worlders by misrepresenting what the contracts state.” It’s just what happened.

And its not like the selective enforcement was random.

It is no coincidence that the rules against fraud were ignored while rules against property theft were enforced.

The rules, the system of gates and switches, were designed consciously to favor property owners over all other interests.

This also brings to mind the comment that black people generally don’t favor socialism or libertarianism, the economics and mechanistic theories of government, because they have personal experience that the application of blind mechanisms never is blind.

@tod-kelly

Well, yeah. But that’s the rub, isn’t it? How you want everyone to behave under your political philosophy and how everyone actually behaves aren’t always the same thing.

The real difference is an ideological commitment to enforcing laws against fraud and the real-world fact that there are too many instances where regulation prohibiting certain kinds of fraudulent activity from ever taking place is a far better solution than believing that a fraud prosecution is a successful deterrent against bad behavior, especially in situations with significant private imbalances.

An ideological commitment to using the government to prosecute fraud by itself is nice in theory but not worth the paper it’s printed on in the real world if successful fraud prosecutions for truly bad acts are difficult to get.

Speaking as a libertarian, I think the standard fare libertarian response to fraud is bullshit. Truly. Fishing. Awful.

Laws against fraud were really helpful with Ashley Madison, weren’t they?

“Your adultery promoting website doesn’t actually have any girls on it!”

“whatcha gonna do, tell the police?”

Wasn’t a lawsuit just filed?

Oh, probably. But they’re making money off that too, doncha know.

You have scam artists, and then you have clever scam artists.

The general business plan is “suckers don’t learn” — fold the scammy parts of the business (there is an actual real dating service for real people. one doesn’t have a treehouse in Manhattan simply for a scam), and start again using a new name — and all the old mailing lists.

I largely agree with this, but I also think there’s something more fundamental at play.

To continue to pick on Communism, proponents of that philosophy are 100% right that, on paper, the ideology is in no way a brutal and totalitarian idea. It’s just that, in practice, when you set up a system that temporarily gives people ultimate power and control, it shouldn’t be overly surprising when those in control continually decide that the time to cede the power hasn’t quite arrived yet.

There is a similar dynamic that goes on with libertarianism, I think. If you have a political philosophy that has a premise that government oversight is a (sometimes necessary) road to Bad Things that should be distrusted and only used when absolutely necessary, it shouldn’t be too surprising when, in practice, the philosophy is used as a justification to spurn oversight that actually is necessary, even by libertarianism-on-paper’s standards. Not because FYIGM, or because libertarians are bad people. Because any system that is likely to want less government oversight over corporations is simply going to have more instances of corporations making immoral rather than amoral decisions over longer periods of time, when those decisions lead to more revenue or profit. I honestly don’t see why this belief is controversial.

And even though libertarians here seem to be taking offense at this idea, know that this isn’t really a slam against libertarianism. All political philosophies have their weaknesses and blind spots, those preferred slivers of influence that allow, in practice, greater potential evil than other philosophies under X conditions, even when it says on paper that it won’t.

Communism, in practice, got exuberant with the idea of punishing people who defected in the iterated prisoner’s dilemma created by the system.

Libertarianism, in practice, seems to have zero tools to deal with people who have enviable positions and use those enviable positions to bargain for the dignity of others (others who have nothing to bargain with but their dignity).

There is an argument that there is a social contract and the person from the enviable position is somehow defecting by bargaining for another’s dignity does not necessarily make perfect sense because, after all, the person who has nothing to bargain with but dignity can take it or leave it. I’m not quite sure what to think about this argument.

@ Jaybird

Are you saying there is no means of deconstructing a enviable position?

There are many enviable positions.

Some of them are the result of chance, some are the result of hard work, some are the result of gaming the system, some are the result of cheating the system.

And, more than that, it’s possible to say that someone only is able to work hard because of chance, someone gaming the system is really cheating it, someone cheating it is really doing his or her version of working hard, and so on and so forth.

And people are usually going to argue some variant of “hey, I did what I did by working hard!” and “hey, that other person did what they did by being lucky enough to cheat the system and make it only look like they were just gaming it”.

Do enviable positions involve voluntary or involuntary exchanges? I can see involuntary exchanges there could be no recourse to deconstruct the position, but voluntary exchanges there should be some degrees of freedom to deconstruct the power of the position.

At this point I’m going to be stuck talking about Foucault.

Like a jerk.

Every exchange is likely to involve a difference in power. If we’re lucky, both people have enough power to make the difference in power negligible to the point that we’re arguing here.

We’re probably not lucky, though. Which gets us to stuff like the ultimatum game, the dictator game, the public goods game… and a setting in which all of these games are iterated.

@jaybird

Libertarianism, in practice, seems to have zero tools to deal with people who have enviable positions and use those enviable positions to bargain for the dignity of others (others who have nothing to bargain with but their dignity).

Based on my recollections of the libertarian arguments of the causes of the 2008 crisis, they seem to have zero tools to allow them to accept the fact that the private sector, especially in finance, is a far greater threat to the global economy than any government could possibly be.

The ignorance coming from libertarians and conservatives, especially those opposing TARP on ideological grounds and those pinning the whole thing on the government, was beyond anything I could stomach.

I’ll leave it at that before this conversation becomes a blood bath. As a rule, I ignore these kinds of conversations, but some of this is getting under my skin today.

@tod-kelly

Because any system that is likely to want less government oversight over corporations is simply going to have more instances of corporations making immoral rather than amoral decisions over longer periods of time, when those decisions lead to more revenue or profit. I honestly don’t see why this belief is controversial.

I co-sign.

Imagine a scenario where low-wage workers in dangerous occupations accept as a condition of employment caps on worker’s compensation in the event of injury. It may be voluntary, but we know how something like this is going to end. Those “immoral” acts are going to involve negligence and possibly illegal actions that directly threaten the safety of workers. Given that they’re low wage workers that agreed to a certain cap, the odds of them getting more are next to nothing. Also, given that they’re low wage workers without the resources to pursue successful tort claims against a company’s negligence, even if there is an actionable claim, the chance that those less fortunate can wage the fight to get just compensation for the harm caused by the company is next to nothing.

I’m not saying that every private power imbalance requires a legislative solution, but it’s clear that some of them do, especially when that imbalance goes well beyond the negotiation of a contract. There’s the threat to worker safety as well and the belief that workers are powerless to do anything to stop companies from behaving as they damn well please. How does a crippled worker with no financial resources get what he/she deserves?

Paying homage to government’s rule in enforcing the law against acts of force or fraud is a completely tone deaf response that doesn’t even begin to address the problem here.

I guess we would have to mention a little bit here about how/if government has the capacity to morally choose winners and losers as well? And whether it is consistently capable of fulfilling that requirement.

@joe-sal

I fail to see how this is either an issue of morality or an issue of picking winners vs. losers. This is about addressing specific problems.

John Oliver had a bit on the oil boom in the Dakotas and he touched on how companies are skirting worker safety. This is one area where, thanks to the human inability to properly parse risk, regulation is very useful.

And I’m saying libertarianism recognizes this as a reality & that it is a problematic point. Bad actors will act badly & government has to exist to act as a (hopefully) impartial arbiter of disputes. It sounds like CNMI was specifically set up to hamstring the ability of any government to fulfill its function in any real capacity.

Which dovertails into @switters comment below. He’s right in that, in an ideal system, enforcing contracts would be doable on a case by case basis. But nothing is ideal, so less than ideal solutions have to be found, like regulations governing what can & can not be in contracts, etc. because the case by case is just not practical.

Remember that libertarianism isn’t (despite what some shallow libertarian thinkers believe) about the anarchist or minarchist state, but about agitating for the minimum amount of government necessary to keep the system functional while maximizing liberty. So it can accept the need for contract regulation in order to make enforcement efficient while at the same time questioning if the current state of such regulation is becoming too granular & unwieldy.

A system that sells labor contracts through fraud & prohibits any kind of redress seeking isn’t a libertarian ideal, it’s more of an corporatist/oligarchical ideal. It is clearly robbing people of liberty in multiple ways, against their will.

@oscar-gordon

A system that sells labor contracts through fraud & prohibits any kind of redress seeking isn’t a libertarian ideal, it’s more of an corporatist/oligarchical ideal. It is clearly robbing people of liberty in multiple ways, against their will.

I agree, but if a libertarian like yourself believes that the appropriate response is to use the rule of law to punish the act of fraud, I would disagree. That requires people with far less power and resources to go after those with the power and resources through a costly process to get what they should be entitled to. Where’s the justice in that? More needs to be done.

I know I’m putting myself at risk of sounding like one of the resident liberals (noooooooooooooooooooooooo) despite my more libertarian preferences, but even I have my limits.

@dave

Which is why I signed onto Switters comment. The system is too large, the gaps too big, to trust to civil claims for every bad act. Even if the courts delivered perfect justice, the sheer volume of potential claims would swamp the system or force us to deploy extreme resources to meet the demand. Efficiency must be sought & one way to achieve that efficiency is through regulation. In this domain, (as I have said many times) my interest is not in minimizing regulation as a goal in itself, but in seeking optimal efficiency, largely by questioning the assumptions used to develop the regulation (questioning Chesterton’s Fence, as it were).

@oscar-gordon

Got it. We may have more in common than I thought. My apologies.

Some may recognize the role, but I think there is less agreement on the means the government should use to police and enforce laws against fraud. And because that lack of agreement, even leftist policies to police fraud are often lumped in with all the other nanny state BS

Because the people signing these can’t read, the contracts could very well have all the horrors we now notice baked in. They could include pay rates of a 1$ a day. And exorbitant travel expenses with 20% interest rates that take years to pay back. And living conditions that many would consider hellish. And insurmountable requirements to qualify to get your passport back and go home. And on and on. So to stop that, you can either set some baseline conditions that must be met (i.e., employment laws) or you look on a case by case basis to determine if there was fraud. And that gets a lot harder than you think once you get down into the weeds. You can bet the contracts have an “entire agreement” clause that says all the terms being relied on are in the contract, and that there were no other promises made to induce execution. There is probably a clause that says you’ve been given an opportunity to consult a lawyer and that you understand all the terms in the contract. Probably a clause that you submit to the jurisdiction of Mariana Islands, and their corrupt court system. So even if one of them was promised a good wage and decent conditions prior to signing the contract, it wouldn’t matter. And some might say it shouldn’t. Wouldn’t most libertarians be on board with the general rule that understanding the terms in the contract is the duty of the party entering into it.

So one of the points I am getting from Todd (perhaps indirectly or unintentionally), and one that I agree with, is that in the beginning, if some left leaning think tanker started pointing at all the ways this could go off the rails, and using those potentialities as reasons why there needs to be some baseline set of rules about employment conditions or contract interpretation and enforcement, he would be just as likely to hear all the nanny statist accusations a lot of regulation proponents hear today. But now, when it has gone off the rails, in large part due to failing to admit those potentialities, we hear from those same libertarians (again, not you) that well, its just a failing of government to provide one of its core functions, which is to police fraud.

@switters

Wouldn’t most libertarians be on board with the general rule that understanding the terms in the contract is the duty of the party entering into it.

It is completely reasonable to expect the government to have a role in creating reasonable rules to require that transactions are conducted in as transparent a fashion as possible and to prohibit one party from acting in a way to willfully and deliberately deceive someone in order to get someone to agree to a certain set of terms.

Seems ok to me.

That would be a big step. I can’t count how many times I’ve had a contract with an insane term put in front of me me and had the conversation go like this: