The drizzle had stopped again. I walked east to stretch my legs, hoping against hope to see my savior’s headlights. The AAA automated message promised me rescue in an hour, a bit before 11, which I thought was hilarious. I’d be walking myself if help was that close. If someone showed up before three in the morning, I’d count myself lucky.

Maui, 2000:

There was literally no shore left. The water went right up to the cliff. It looked deep, too.

No paths up the cliff on this side of the pool; that’s why I’d walked all the way over in the first place. The cliffs were quite steep, although sandy, and covered in trees growing sideways. Thin trunk trees–bamboo, maybe? No, bigger than that. Maybe eight inches circumference, a little more.

How unfair. First I lose my camera case. Now I’m stuck down here at high tide in the late afternoon. What next?

How unfair. First I lose my camera case. Now I’m stuck down here at high tide in the late afternoon. What next?

(The stock photo, stamp and all, shows the cliffs and the high tide I was facing)

Clearly, I’d have to climb up the cliff with the sand and the trees. I took one more look around for my camera case before reluctantly abandoning my search. The minute I started climbing I was vertical, my feet sinking into the deep sand, stopped by tree roots. Hoisting myself up and forward by grasping a new tree trunk, I decided this wasn’t too bad. Work, but still, it’d be an easy enough climb. Maybe I should have stayed a little bit longer to look again for the case. I turned to scan the ground one more time, now about 15 feet up, while reaching for a trunk. Except I missed the trunk, lost my balance, and was, shockingly, entirely airborne, feet desperately searching for ground, body pitching backwards….

WHAM!

Into something hard, air knocked entirely out of me, feet driven down into the sand, looking straight up into a sea of tree trunks, whooping for breath, still holding onto the branch I’d grabbed on the way down. But how could my feet be in the sand when nothing else was? What was holding me up? Why were my shoulders bent back, with nothing supporting them? Slowly, dimly, it dawned on me I was suspended in mid-air, ten feet off the ground, back balanced on a thin tree trunk. I instinctively grasped for my fanny pack which was, thankfully hugging my front at the moment, so my camera was ok. Bad enough I don’t have the camera case, but…

and that’s the first time I said aloud, “Eastern 401.”

Situational awareness. Maintain focus on your primary objective. Airlines made the Eastern training video to remind pilots of these essential responsibilities. Until that moment, I thought my biggest problem was the lost camera case. But if I didn’t give up on the camera case, I’d be flying my plane right into the ground. Let the camera case go. Choose between a night spent on a remote beach in Maui with an inbound tide or climbing this cliff without getting killed.

Situational awareness. Maintain focus on your primary objective. Airlines made the Eastern training video to remind pilots of these essential responsibilities. Until that moment, I thought my biggest problem was the lost camera case. But if I didn’t give up on the camera case, I’d be flying my plane right into the ground. Let the camera case go. Choose between a night spent on a remote beach in Maui with an inbound tide or climbing this cliff without getting killed.

I considered my options. The cliff still looked good. But I had to focus.

Time for a Hoosiers. “After I climb up the cliff, I’ll buy a camera case at the first open store I see.” By the time I finished my grueling climb up the cliff, the sun was  setting. I wobbled back to my car, legs shaking, exhausted and thirsty, and drove off the dirt track back to the highway. A few miles up the highway, I stopped to catch my breath again. A lovely older couple was there, capturing the sunset. When the wife saw my sandy jeans and scratched arms, she insisted I lean back on the hood of their car to drink an ice cold bottle of water she gave me. I can still remember how good it tasted. All the stores had closed by the time I got back to town, but I bought a little canvas camera case with pockets before breakfast the next day.

setting. I wobbled back to my car, legs shaking, exhausted and thirsty, and drove off the dirt track back to the highway. A few miles up the highway, I stopped to catch my breath again. A lovely older couple was there, capturing the sunset. When the wife saw my sandy jeans and scratched arms, she insisted I lean back on the hood of their car to drink an ice cold bottle of water she gave me. I can still remember how good it tasted. All the stores had closed by the time I got back to town, but I bought a little canvas camera case with pockets before breakfast the next day.

My son accidentally dropped the camera a decade ago. I still have the case.

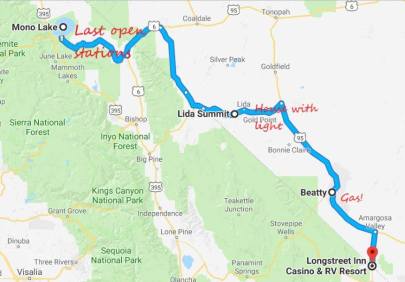

Situational awareness, Nevada, June 2018: My overriding goal had been finding a gas station before I ran on empty. But ultimately, the gas is just a tool in task of driving a car which, like flying a plane, is always the primary objective. When barreling down a dark road at sixty miles per hour in a 2000 pound block of metal, success is defined first of all by not killing myself nor any large bovines.

As I drove by the Esmerelda station, closed up for the night, I was down to 35 miles and one hope. Could I make it to US 95, about 45 miles away? There had to be a gas station at the junction. I called AAA one last time as I went through Lida Summit. Every time I lost contact, I ended up with a different agent but spent very little time catching each one up. I envisioned them calling out to each other, “Hey, there’s some lunatic woman in the Nevada desert about to run out of gas. Let’s not lose track of her.”

The cell signal was beautifully clear as the most recent agent gave me the bad news: at the US 95 junction, there was gas 25 miles north, and 40 miles south. Fifty and seventy five miles away from my current position.

What the hell, Nevada?

Just as AAA gave me this terrible news, I came upon a brightly lit house, with a forbidding fence all around it. It’s the only house for dozens of miles in either direction (I easily found it later in Google’s satellite view). Time: 10:45. Miles remaining: 16. I took the house and the light as a sign, and pulled the trigger, asking AAA to bring me 5 gallons of gas.

Just as AAA gave me this terrible news, I came upon a brightly lit house, with a forbidding fence all around it. It’s the only house for dozens of miles in either direction (I easily found it later in Google’s satellite view). Time: 10:45. Miles remaining: 16. I took the house and the light as a sign, and pulled the trigger, asking AAA to bring me 5 gallons of gas.

So I had little to do save listen to Sirius, look at the night sky, feel the misty drizzle, and mull on the circumstances that brought me to this starry, isolated spot.

I made sure to count my Garfields. For 35 years I’d ignored everyone who sang paeans of praise to AAA. But two years earlier, I’d randomly joined when I asked my brother for a jump and he said “Oh, hell, that’s what AAA is for.” Without their dedicated service, I’d probably be sleeping back at the Esmerelda station, waiting for morning. My hotel clerk commiserated with my plight and promised to wait up. I’d finally made it over Sonora Pass. Three deer had crossed the road.

Best of all, I wasn’t lasting out the night eighty miles back with one dead car and two dead cows who hadn’t made it across the road, awaiting the arrival of one angry rancher while trying to explain the circumstances to an unsympathetic insurance company, with the only possible upside being a guest role on a JK Simmons commercial.

In fact, it took only three hours for my AAA hero, a ridiculously cheery guy named Ben, to find me with eight gallons of gas. He cheered me up by telling me he’d passed four cars since turning off Highway 95 onto 266. I’m not the only idiot, I guess. One woman flagged him down begging him desperately for help, he said, his normally cheery face clouding briefly.

I told him to stop at five, and give the rest to her. He demurred, telling me I had seventy  five miles to get to Beatty, and he wanted to be sure I had plenty to spare. We compromised at six, which put the mileage back at 125. As I started up the car and thanked him profusely, apologizing for waking him, he warned me to watch out for the donkeys in Beatty. I laughed at the joke–but no, he emphasized, burros in Beatty are kind of a thing. Clearly, this was my trip for cloven-hooved threats.

five miles to get to Beatty, and he wanted to be sure I had plenty to spare. We compromised at six, which put the mileage back at 125. As I started up the car and thanked him profusely, apologizing for waking him, he warned me to watch out for the donkeys in Beatty. I laughed at the joke–but no, he emphasized, burros in Beatty are kind of a thing. Clearly, this was my trip for cloven-hooved threats.

The long drive to Beatty wasn’t too bad–the burros, unlike the cows, must have been sleeping. The last 45 miles to my hotel, a little casino resort I’d first found on the Death Valley trip that saw Pass Attempt #1, were grueling. I pulled in at 4:15 am, was in bed before 4:30, and woke up at 9:15 for breakfast. Back on the road before ten o’clock, on to San Juan River.

Driving through Virgin River Gorge on day 2, I called my dad and told the tale.

“So you ran out of gas.”

“Well…yeah, I guess that’s the short version. Seriously, Dad, I think Google Maps should warn its drivers.”

“You need to stop relying on those damn phones to drive.”

“A map wouldn’t have helped. Look, Google has the time; it has my destination, it knows I’m driving. It could just say “warning! There are no open gas stations on your route for 200 miles. It’d be easy.”

“You know what else would be easy,” my dad said. “You could get a gas can and keep it in your trunk. Fill it up for road trips.”

Yeah, I’m…not much of a planner.