It’s a belabored point, but one that needs occasional repeating: TGIF is the eunuch of end-of-workweek acronyms. Thank God It’s Friday? I respect the devotional aspect, but His touted support for self-helpers makes this seem a bit passive. Now, POETS. That’s a call to action, clarion to the rugged individualists, crisp and energizing as a winter’s morning. Piss Off Early, Tomorrow’s Saturday! TGIF is the ice cream social your parents organize for you and your school chums. POETS Day is the kegger you detonate when Mom and Dad are out of town. Leave TGIF for office coordinator emails with stock art balloon borders and posters of that long-dead kitten. Put aside childish things. You know the drill. Dissemble, obfuscate, fudge the truth, and gleefully trespass the norms and delicate pieties that preserve our hopefully durable civilization. Nearly all means are justified by the need to prematurely escape the bonds of employment and settle in at a friendly neighborhood joint a few hours before happy hour begins, lay comfortably in the grass at a local park with a special someone, go for a swim, catch a matinee, or for the masochists, go for a light jog. It’s your weekend. Do with it as you will, but in homage to the mightiest of all acronyms may I suggest setting aside a moment for a little verse? It’s a particularly good way to pass time waiting on friends who may not run as roughshod over the delicate pieties and were not as successful as you were in engineering an early exit.

***

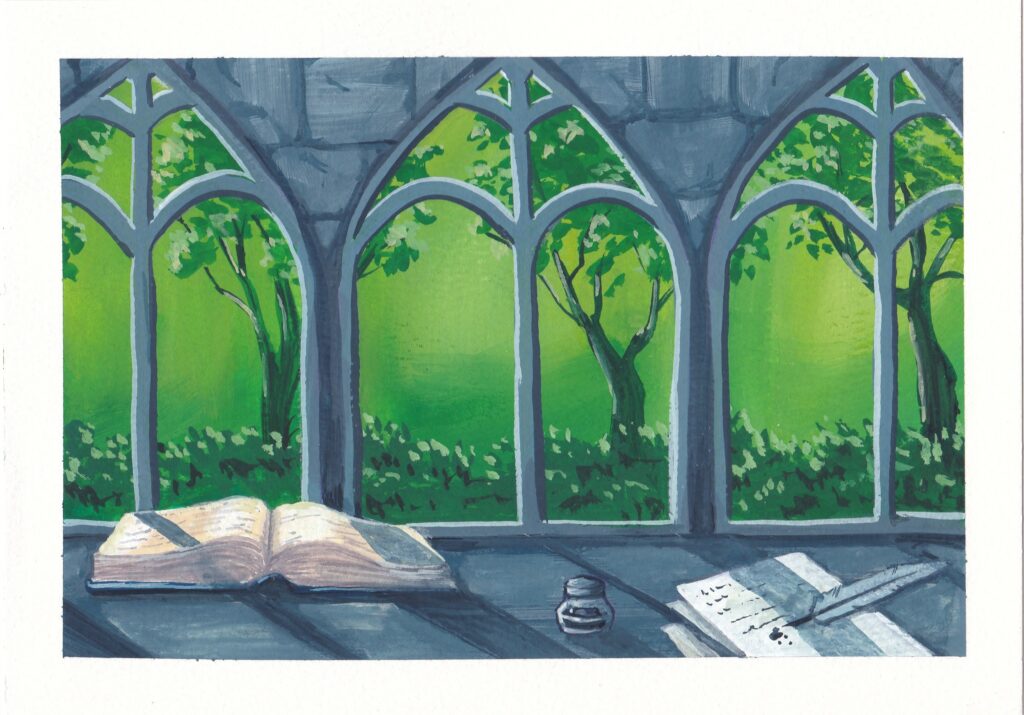

When most people think of a poet, what one looks like as they go about their business, they probably think of someone Byronic leaning over a battered wooden table, scribbling mid inhale on a loose sheet of paper, fingers inkpot stained, a girdle-tight vest over whatever style puffy shirt the modern mind thinks was always in vogue before mass produced mirrors, a vee of dark curls fopping over the upstage eye like a bunch of wine grapes, the interior of the tent improbably well lit by a single candle, and the air still redolent of gun smoke from day’s battle for Greek independence. Poets may not be of the Romantic school, but we think they should look like they are.

Wallace Stevens woke each workday and walked from his home in West Hartford to his office at the Hartford Accident and Indemnity Company downtown, composing poems as he went. After settling in behind his desk, the first order of business was to summon his secretary, to whom he’d dictate whatever poems he wrote on that morning’s commute. She’d type them up and put them in a drawer for him and over time he’d sort through, keeping the ones he liked and tossing the rejects in the trash. As Yale Professor Marie Borroff said, “Oh, to have his wastebaskets.” He didn’t strike much of a Byronic pose. He didn’t even strike a Georgina Rossetti pose, but he was passionate.

At a favorite holiday spot in Key West, he got into a voluble argument with Robert Frost on at least two different occasions, and once he slugged the man he considered the anti-poetic devil. Per Stevens biographer Paul Mariani, “So it began, with Stevens swinging at the bespectacled [Ernest] Hemingway, who seemed to weave like a shark, and Papa hitting him one-two and Stevens going down ‘spectacularly,’ as Hemingway would remember it, into a puddle of fresh rainwater.” He did manage to land at least one blow, apparently breaking his hand on Hemingway’s jaw.

Stevens has been described as a hard poet to read mainly because he dives deeply into philosophy. His early work espouses subjectivism, which he claims to later abandon in favor of realism, but his realism relies on a rewriting of the definition of reality to fit his tastes so it’s not. It’s stealth subjectivism and just like every other form of that philosophical bent, is just a waypoint before fessing up to nihilism. Thankfully, he’s a happy nihilist. His poetry is often comic or satirical.

Gubbinal

Wallace Stevens (1879 – 1955)

That strange flower, the sun,

Is just what you say.

Have it your way.

The world is ugly,

And the people are sad.

That tuft of jungle feathers,

That animal eye,

Is just what you say.

That savage of fire,

That seed,

Have it your way.

The world is ugly,

And the people are sad.

“If the world is as you interpret it, why not make it a happy place?” he chides.

His philosophy is full of contradictions if you look at his body of work. There is no God. God and poetry are equal. Reality is the product of the imagination. Reality is not knowable. That the imagination interprets an external objective world presupposes an objective world whose existence he seems to both deny and acknowledge. His philosophy as expressed in his poetry does make sense if you see his body of work as a self-correcting search rather than a statement. Rather than allowing the contradictions to upend his world view, he seems to force himself uphill by recognizing errors, tweaking, recognizing, and tweaking again.

Stevens appears to have a need for religion even though he’s rejected it. There’s an absence he feels. “After one has abandoned belief in God, poetry is that essence which takes its place as life’s redemption,” he writes in the collection Opus Posthumos. He refers to his need to replace God with what he calls a “Supreme Fiction.”

A High-Toned Old Christian Woman

Wallace Stevens (1879 – 1955)

Poetry is the supreme fiction, madame.

Take the moral law and make a nave of it

And from the nave build haunted heaven. Thus,

The conscience is converted into palms,

Like windy citherns hankering for hymns.

We agree in principle. That’s clear. But take

The opposing law and make a peristyle,

And from the peristyle project a masque

Beyond the planets. Thus, our bawdiness,

Unpurged by epitaph, indulged at last,

Is equally converted into palms,

Squiggling like saxophones. And palm for palm,

Madame, we are where we began. Allow,

Therefore, that in the planetary scene

Your disaffected flagellants, well-stuffed,

Smacking their muzzy bellies in parade,

Proud of such novelties of the sublime,

Such tink and tank and tunk-a-tunk-tunk,

May, merely may, madame, whip from themselves

A jovial hullabaloo among the spheres.

This will make widows wince. But fictive things

Wink as they will. Wink most when widows wince.

He uses the palm as metaphor for man or man’s conscience with the winds as experience of the world or ideas blowing through and playing the fronds like a musical instrument more than once. In “Of Mere Being” one stands at the end of existence and there the wind is blowing “softly.” In this poem there is a different song that he describes as “without human meaning, / Without human feeling,” but it’s coming from what is clearly a phoenix. Why would a man who has rejected the afterlife include an image of rebirth in a poem about death?

I think the phoenix was not for him, but for his ideas. His philosophy dies with him, but in death an undeniable truth – that second song sung by the bird – about what lies beyond will assert itself. Oblivion or immortality will be realized from the ashes of his reasoning.

Of Mere Being

Wallace Stevens (1879 – 1955)

The palm at the end of the mind,

Beyond the last thought, rises

In the bronze decor,A gold-feathered bird

Sings in the palm, without human meaning,

Without human feeling, a foreign song.You know then that it is not the reason

That makes us happy or unhappy.

The bird sings. Its feathers shine.The palm stands on the edge of space.

The wind moves slowly in the branches.

The bird’s fire-fangled feathers dangle down.

After Stevens’ death, Fr. Arthur Hanley claimed to have presided over his conversion to Catholicism months before Stevens died. There was only a nun to witness this claim, and Steven’s daughter Holly denies it ever happened.

Thankfully, he’s a happy nihilist.

Let the lamp affix its beam.Report