Choice, not Chance

by zic

In November 2012, a splattering of headlines declared that the UN called contraception a universal human right. in a new report, By Choice, not by Chance

When a woman is able to exercise her reproductive rights, she is more able to benefit from her other rights, such as the right to education. The results are higher incomes, better health for her and her children and greater decision-making power for her, both in the household and the community. When women and men together plan their childbearing, children benefit immediately and in their long-term prospects.

This is the first time the UN had ever referred to contraception as a universal human right; and the report’s Executive Summary, written by Dr. Babatunde Osotimehin, the executive director of the UN’s Population Fund, lists the compelling outcomes that justify viewing reproductive or family planning rights as a universal human right, one with implications for women, children, and also men. But our fraught debates about religious rights vs. reproductive healthcare indicate reproductive-healthcare rights are not perceived as universal in the United States, reproductive rights are not accepted as an inalienable right, and there is no compelling force behind the UN’s suggestion that should be.

Many people, organizations, and nations perceive reproductive healthcare as trampling natural moral law. Andrew M. Greenwell, Esq. responded to Dr. Osotimehin as in Catholic Online:

“Family planning is a human right,” wrote Dr. Osotimehin. “It must therefore be available to all who want it. But clearly this right has not yet been extended to all, especially in the poorest countries. Obstacles remain. Some have to do with the quality and availability of supplies and services, but many others have to do with economic circumstances and social constraints.”

By this latter, Dr. Osotimehin certainly has in mind the Catholic Church and the natural moral law. He has previously commended Melinda Gates, and her decision to use Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to expand the reach of artificial contraception in the heartland of Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia in direct contravention to the Catholic Church’s moral teachings.

Dr. Osotimehin seeks to spend an extra $4.1 billion a year to make family planning available to anyone who wants it. “Family planning is still more akin to a privilege enjoyed by some rather than a universal right exercised by all.”

Dr. Osotimehin is morally obtuse: “Women who use contraception are generally healthier, better educated, more empowered in their households and communities and more economically productive. Women’s increased labor-force participation boosts nations’ economies.” He is oblivious to how contraception tramples traditional values, social conventions, and, what is more, the natural moral law.*

He does not seem to care about the vice such contraceptive technology institutionalizes and normalizes, and how it mars human sexuality. He is nothing but a mouthpiece for a secular liberal worldview.

It’s “obtuse,” Greenwell says, to help expand contraception use; it’s obtuse to lessen the social constraint. I can’t help but wonder what he thinks of the rape or sexual coercion that one out of three women experience. I wonder what he thinks of Savita Halappanavar, who painfully died of sepsis in an Irish hospital in 2012 because the staff refused to abort her pregnancy. Was this tragic loss in keeping with the morals of social constraint? I he doesn’t really consider the thousands of women in Ireland banished from their families to group homes where they delivered their illegitimate babies, and who were then sold into indentured servitude, forced to leave their newborn infants behind. I imagine he holds high regard, rightfully, for the good-hearted the nuns who nursed these women through their pregnancies and deliveries, who cared for, raised, and buried their bastard children in unmarked graves, because (despite the hyperbole) their charges were baptized and buried in accordance with the social restraint reserved for bastard children.

Social restraint can lead to evil outcomes, too.

Here in the United States, we are blessed to be one of the first places where a majority of women have had general access to modern reproductive health care, including contraception and abortion. Griswold and Roe v. Wade opened the doors for reproductive healthcare as medical privacy, but social constraints still present significant barriers for many women, particularly for women who live in poverty. PPACA, or Obamacare, requires identifying the essential healthcare needs particular to women that had been underserved; and it mandated providing basic, preventive services without co-pay, for services where women’s essential needs went unmet. And thus the contraceptive mandate was born; a legal compulsion to end discrimination against women in health insurance to cover women’s reproductive healthcare needs that aligns with the UN’s call to consider reproductive rights as a universal human right.

I’ve lived through this change; I was born in 1960, the last “official” year of the baby boom. I think it would be pretty safe to attribute the end of the baby boom to birth control pills, which were approved for use in the United States in 1960 after a breathtaking race for a scientific breakthrough in hormonal contraception.

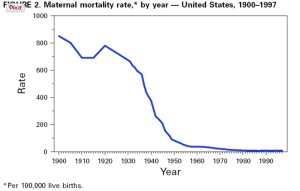

My great grandmother died in childbirth. It’s likely some of you have grandmothers or great grandmothers who did, too; maternal death being common up through the end of the 1800s. Thankfully, maternal health care has advanced radically, and we don’t live in Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights world, where all the mothers are either already dead or at risk from of pregnancy and birth.

My grandparents all came from big families, of four or more children; my paternal grandmother had nine brothers and sisters. I’m the middle of seven pregnancies my mother had, and my peers in school also had big families; back in the day, being an only child was weird. As families got smaller, women could get educations and enter the work force, one of the primary factors leading to the growth in the US economy over the last 50 years:

My mom gave birth to my oldest sibling in the early 1950s. She was just barely 16, and had just finished her freshman year of high school. An abortion would have been a dangerous and illegal affair; girls “went abroad” only if they were wealthy enough. They had polite shotgun weddings if they had family that marginally stood up for them. Failing that, they became mothers with bastard children, pretty much abandoned by society. My mother had a second child a year after the first, and a third two years later, a girl born with “severe spinabifida” — the family terminology – my mother told me they didn’t feed her in the hospital, and she starved to death after three days. Then I came along, born in 1960, the year of the pill, and the end of the baby boom. Another sister died two years after me, also from severe spinabifida, also likely from starvation. The next boy would also have died just a year or two earlier. He was born with a birth defect, not spinabifida, and after major surgery (done without anesthesia,) he survived; and the last of of her children was healthy, though we lost my baby brother from an allergic reaction to the AIDS cocktail in the late 1990s.

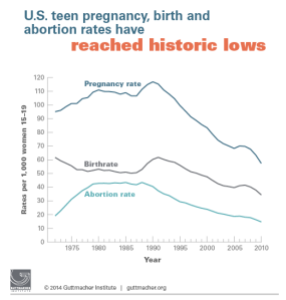

According to the CDC, “The average fertility of women in the United States was about seven children at the beginning of the 19th century, it declined slowly and by 1960 it was 3.7 children per woman. Fertility in the United States dropped to its lowest point in 1976 at an average of 1.7 children per woman and has remained relatively stable at around 2.1 children per woman.” My mother had seven children, the first at 16 and the last when she was 34. Now she’s 75 and a great-grandmother, and during her lifetime, family size has dropped significantly, to an average of 2 children. The rate of teenage pregnancy, abortion, and birthrate has declined significantly since peaks in the 1990s:

1960 was the year things changed in so many other ways. Before, very few women become doctors, lawyers, politicians, business owners. During WWII, women had shown they could run factories to build tanks and planes, but those who worked went back to being maids, waitresses, teachers, nurses, secretaries, and most went back to the home and settled in for the Ozzie and Harriet life. When the pill hit the markets, a woman’s right to vote was barely a half-century old. That last is important to remember, because women’s rights rests on two thousand years or more or religious and social tradition that dictates women must be chaste and sexless to everyone but her husband, or she will potentially burn in hell. Her private property rights were flimsy and often non-existent. One of our most sacred social ceremonies, the wedding, stars the bride on her big day as her father gives her to her husband, a transferal of property. Before the awakening in the mid 1800s, women’s voices are almost completely missing from our written history and literature; more than two thousand years of words written down by 99.999% men, who often mansplain stuff they know nothing about.

You can’t have read this far without expecting something on the Supreme Court’s Hobby Lobby decision. My strongest objection to the Supreme Court’s decision is the misappropriation of conscience. A woman’s conscience, to do as she sees fit in accordance with her beliefs, is her own — particularly when she’s exercising her right to make private medical decisions about legal medical services. Funny thing is the data shows when women have the right to contraception, moral outrage to the contrary, women have demonstrated that, for the most part, they act morally.

Belief in any religion is voluntary. Community religious norms of female sexuality can be coercive (purity promise or you’ll burn in hell), and sometimes lethal (honor killing of rape victims or failure to perform a live-saving abortion), and As Greenwell shows above, religious social conservatives clearly understood that their religious norms are in conflict with the UN’s declaration. Contraception is a universal human right because it’s part and parcel of the right to bodily sanctity; and without it, women can never be fully equal. The weight of history provides evidence of thousands of years without women partaking of that history except as bystanders, reflections of the men who held the power.

It’s easy to be distracted by the question of “who pays,” because the Greens framed this as an exercise of their religion by refusing to pay for insurance they consider morally objectionable because it may cause an abortion. But this is not just a question about who pays. It’s a question about “who says.” It’s about who’s morally responsible, about just who is committing women’s perceived sins. The question extends beyond Hobby Lobby, to who is complicit in sin by doing something like providing comprehensive reproductive coverage, under the guidelines of U.S. law. The Greens are players in a long game about setting legal precedents about who says what kind of reproductive rights women can have. Their side would have that say shaped by their religious beliefs.

Ironically, women use contraception responsibly. We get all het up about the girlz gone wild, but the average family size of seven when my mother was in her childbearing years has dropped to two, which is how many children I have. Women’s responsibility is proven by the drop in teen pregnancy, family size, abortion, and by increases in education, career success, and economic well being.

The numbers of unmarried mothers are distressing, but calls for considering other things, including the importance of all people’s exit rights from marriage, the burden here on men to be better fathers and husbands, and a justice system that turns far too many fathers into felons for non-violent crimes. It is unfair to hold a discussion about single mothers without also considering the barriers to contraception and legal abortion so many women face, since this falls predominately on the poorest women in the US.

The numbers of unmarried mothers are distressing, but there’s some burden here on men to be better fathers and husbands. Women at least no longer need to spend their lives trapped in bad marriages, and we should also blame the justice system for turning far too many fathers into felons for non-violent crimes. It is unfair to hold a discussion about single mothers without also considering quite a few other things, including the importance of all people’s exit rights from marriage, and the barriers to contraception and legal abortion so many women face.

So my objection here is not about a question of access – we can achieve access to contraception with a myriad of different ways. My objection is to the war on the right to access, and that war flows mostly from religious belief, firmly established with Hobby Lobby’s victory in court.The weight of all history previous to the pill proves the point that without contraception, women cannot be equal. I don’t care what Greenwell writes or if the Greens tell their employees that they think certain forms of contraception are sinful; they have the right to free speech But I take deep offense when anyone tries to enshrine infringements on women’s human rights into law.

Women’s equality is a very new and precious thing. It’s a change that disrupts, no doubt. And I do feel some sympathy for those who feel threatened by that disruption. But my sympathy doesn’t dint my clear view of the kind of dignified, orderly, responsible life that was impossible before modern contraception. The data shows that it’s a change for the better, too – fewer maternal deaths, fewer infant and child deaths, fewer unplanned pregnancies, fewer abortions, and better economic outcomes.

Women have demonstrated they have, overall, great ability to exercise wisdom in controlling the Wuthering Heights of their fertility. Despite social constraints, women have historically tried to control their reproduction, often in ways that led to their own impairment or death. In communities and states like Texas, were there are high barriers to contraception, women in the United States are also taking matters into their own hands; everywhere, they are still attempting to exercise their own agency over their bodies. Judicial overreach that protects the Greens’ freedom to exercise their religious beliefs risks appropriating women’s reproductive rights based on belief instead of science. To borrow a word from Mr. Greenwell, it’s trampling women’s right to moral self-determination.

My preferred outcome, given what we have for a political system, legal precedent, and statute would be for employees working for corporate objectors to be covered by the government and or insurance companies in a way that seems seamless to the employee; while corporate objectors pay for their objection with a tax penalty exactly as real, non-corporation people pay a tax penalty when they decline to purchase health insurance, thus offsetting the rent-seeking objectors are placing on everyone else. There are two conflicting obligations here, first, not to overtly intrude on someone’s religious practice while second, not to violate another person’s universal human rights. I suspect any resolution that shifts burden from employers to insurers or government might not be will not ease the burden of conscience for some observant business owners opposed to any contraception.

With the advances in modern medicine, we consider the decline of maternal death a great achievement, and most people agree that a threat to the mother’s life provides justification to end a pregnancy. No one wants to see women die like Savita Halappanavar died. We celebrate the declines in infant mortality, as well. I’ll always be haunted by the brutal deaths-by-starvation my two infant sisters, and am grateful for the medical advances that both help identify severely deformed fetuses and help save their lives should their mothers opt to give birth to these children.

I live, every day, with the knowledge that had my mother had access to reproductive health care, including contraception and abortion (and I wish she had), neither I nor my siblings would exist.

Ironically, had contraception been available, there’s also a good chance she would have avoided pregnancy without it; ignorance plays a role in her story. Fourteen and just a few months into menarch, my mother said she asked her mothers where babies come the year before she got pregnant, when her mother gave birth for the last time. “The Indians bring it,” her mother told her, “but they break my leg, so I have to go into the hospital for two weeks.” This is sex education circa 1950, that golden era so many people want to revive. My mother wasn’t taught how to keep her body healthy, she was taught she was supposed to date from this group of good boys, but not that group of bad boys.

Unlike my mother, I chose to marry when I was 20. Contraceptives were readily available, but many of the things ACA calls for today weren’t yet on the market. Becaue of chronic migraine, I opted for less reliable methods, and I got pregnant. We’d been together for nine years, married for five, and would have waited longer, by choice. We decided fate had made the choice for us. Thanks to an inflationary bubble on malpractice insurance for ob/gyn’s in the 1980s, I still lived with indecision and agony over the pregnancy. Doctors were quitting the practice because if increasing premiums, and a lot of women without my high-risk family histories had trouble finding doctors. Because of my mother’s reproductive history, I couldn’t find a doctor; I was an insurance risk, and maternal insurance coverage was optional. Finally, my awesome doctor agreed to deliver my baby if I’d agree to have an amniocentesis, so at 16 weeks, a technician held an ultrasound paddle to my tiny baby bump, and my doctor stuck a giant needle through into my uterus next to the fetus we could see floating on the screen. Tiny heart, fluttering. Spinal measurements, good. But sixteen weeks is far, far too early to see neural-tube defects, and the costly genetic profiling in a 1980’s medical lab took ten long, long weeks to receive; putting an action based on the results of the genetic testing I was required to receive at the end of my second trimester or the beginning of my third. My choice would have been made with consideration of my two sisters, starved after nine months of pregnancy; I would have aborted, and it would have been likely been a late-term abortion. This is a tremendously difficult thing to consider, something I cannot imagine any women taking lightly, something it appalls me that so many people think women do take lightly.

We cannot change what was, I can’t give my mother back her innocence by undoing myself, and I can’t imagine life without my eldest. Yet if I could give my mother the agency to make these choices for herself, in accordance with her own conscience, I would opt to never have been.

To be forced or coerced into pregnancy because someone else’s beliefs interfere with her self-determination absconds a woman’s control of her body. Even worse, it’s absconds with her moral agency; and recognition of that agency is tenuous at best; 2012, when the UN first called contraception a universal human rights, was just a few days ago; 1960 too recent to have aided my mother. Universal rights aren’t earned, but if they were, the facts show that for the most part, women who have access to contraception and reproductive healthcare reproduce responsibly.

Thank you to Jason Kuznicki for his help editing this, any errors you find were introduced with my re-write. His efforts made this a much better piece. (And editors, feel free to correct the grammatical ones, please. I rely on the kindness of editors.)

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FgyGwSGwHdQ]

Great essay, Zic.

It is interesting to note that the Conservative Right has opposed Griswald and the expanding cases since they came out. Just like so much of the modern conservative movement seems to want to unravel any civil liberty advancement that came out of the Warren Court. I think it is the Warren Court that functioned as the catalyst for the modern Far Right movement. Impeach Earl Warren was not an uncommon expression during the 1950s and 60s.

The argument against Griswold is that there is no explicit right to privacy in the Constitution and conservative jurists have always been skeptical of substantive due process analysis or of have expansive 14th Amendment analysis. They would argue that if you want a right of privacy, you need to add one to the Constitution. My general response to this is that the 4th Amendment is basically a right to privacy as are many other Amendments if only implicitly.

I think a large part of conservative resistance to the Warren Court is that it removed or substantially curtailed the moral aspect of traditional Police State powers. Now what is interesting about the liberal and conservative divide in the US is how we tend to focus on different sections of the Police powers (health, welfare, safety, morality) and the differences in what morality means. Liberals tend to use morality as a way of talking about the welfare state.Report

The meanings of words shift over time. My understanding is that in the 18th century you would announce (should you feel the need) your intention to visit the outhouse by saying you needed some privacy. Hence, the slang term “privy” for a restroom. (We can never really bring ourselves to call that room for what it really is, huh? I mean, have you ever taken a nap in one? Unless you were really drunk anyway?)

So the bottom line is that for the framers of the constitution in the 18th century to have written into the Constitution a right to “privacy” would have been to literally guarantee the right to take a crap or perhaps to build an outhouse. Sorta silly, huh?

On the other hand, if one were to search for a word that most neatly encapsulates the intent of the 4th amendment in modern vernacular, I think you would be hard-pressed to find a better word than privacy. I find that particular argument from conservatives to be disingenuous on steroids.Report

I suspect that conservatives would be just fine with privacy as a general concept had it not been used as a foundation for various rights of sexual autonomy like contraception and abortion. The legal notion of a right to privacy received its most prominent early exposition in a law review article by Louis Brandeis. As far as I know, until the Griswold case, conservatives did not take particular exception to the idea that the Constitution protects the right of individual privacy as described in Brandeis’s article.Report

@burt-likko

The legal notion of a right to privacy received its most prominent early exposition in a law review article by Louis Brandeis. As far as I know, until the Griswold case, conservatives did not take particular exception to the idea that the Constitution protects the right of individual privacy as described in Brandeis’s article.

I’d argue that it was implicit in Munn v Illinois. While the Supreme Court upheld a rate regulation on a certain kind of business, it said that such regulations applied to companies “affected by a public interest”. This public-private distinction was applied to state-level economic regulations on 14th Amendment grounds up until the Court eliminated it in the 1934 decision Nebbia v New York. Some of the freedom of contract cases also had an element of privacy to them and, of course, there were the decisions in Meyer v Nebraska and Pierce v Society of Sisters. No explicit right to privacy was recognized but at that time the court wasn’t in the business of identifying rights. It simply state exceeded its power.Report

Do you agree with me, @dave , that conservatives weren’t really all that opposed to the idea of privacy as a constitutional right until Griswold? I’d actually go a step further and suggest that the concept of a strict and narrow reading of the Constitution, grounded in the time-of-adoption meaning of the text, was not one identified with conservatism until right around then, either.Report

@burt-likko

Do you agree with me,@Dave, that conservatives weren’t really all that opposed to the idea of privacy as a constitutional right until Griswold?

I agree. I don’t think it was an ever an issue.

I’d actually go a step further and suggest that the concept of a strict and narrow reading of the Constitution, grounded in the time-of-adoption meaning of the text, was not one identified with conservatism until right around then, either.

Yes, and that’s because right around then, not only did you have the Griswold decision but the Warren Court had really stepped up incorporating the Bill of Rights into the 14th Amendment and it’s equal protection jurisprudence was re-shaping the civil rights landscape.

It was one thing to complain about the scope of the federal power post-Wickard v Fillburn but it really pushed conservatives over the edge when the Supreme Court began protecting rights against the actions of the state governments.

The intellectual framework was already laid out by the time this happened. I think Charles Fairman’s work was one of the more commonly cited texts of that day. However, both his work and Raoul Berger’s work have come under intense criticism.Report

I took the liberty of cleaning up what appeared to be alternating fonts, sizes, and font colors, and tightening up blank spaces, likely to have been the unintended relics of multiple edits on multiple computers, to present the post in the same sort of visual style common for these pages. All my changes were to formatting only save correction of a trivial misspelling.Report

Thank you, this was a beast of a piece to get loaded here; took Tod and I a few weeks (of which we were both much on the road, as well.)Report

The boundaries of the Greenwell quote are not clear. Perhaps there’s supposed to be a nested blockquote, with the Osotimehin quote (which is blockquoted) inside?Report

Thank you, yes; it should end after the word “worldview.”Report

OK, that should be clear now.Report

We should get a spirited debate about the nature of rights from this piece.Report

Ding ding ding ding ding ding ding ding! For your correct guess, @leeesq , you get… unlimited commenting privileges for a week!Report

This seems like would be a line item on the enrollment for the individual employee. Such a line item could be an opt-in or an opt-out, and from there the benefits administrator would determine the employee’s preference and enroll her in some sort of a supplemental coverage program, funded with tax dollars, that would cover the contraception. Now, if those tax dollars funding the supplemental contraceptive coverage come from the tax penalties for providing incomplete coverage, isn’t that still an indirect means of nevertheless compelling the corporate objectors to pay for the very thing that they got the Supreme Court to rule they don’t have to pay for?Report

Yes. But it’s not different from a conscientious objector who, through dint of belief, cannot be conscripted into a combat role in time of war, but is not relieved of the obligation to pay taxes which support defense budgets.Report

Well, I think that’s fine, personally — but I’m pretty sure that five out of nine sitting Supreme Court Justices are not.Report

@burt-likko this is exactly the problem of understanding and empathy that led to the video you posted of Couric’s interview with Justice Ginsberg.

Perhaps it’s time to stop appointing men to the court until the jurisprudence imbalance has been corrected? Personally, I think that would be equally offensive. But I have no problem suggesting that five justices were wrong, every bit as wrong as justices have been in the past with decisions like Dred Scott.Report

Hah. As to the all-women suggestion, Justice Ginsburg herself put it nicely — there’s lots of women she’d be unhappy to call her successor. Like men, women do not suffer from an unanimity of opinion on nearly anything, even contraception.Report

@zic

It seems to me that the real problem here is the artificial and utterly unnecessary connection between employment and healthcare. Arguably this is a point both sides of the Hobby Lobby case should be able to agree on – if employers were not actively incentivised by policy to buy health insurance for their employees the Hobby Lobby case would never have existed.Report

That’s a good article Zic. Kudos for writing it. I object to almost nothing your wrote-no one should be beholden to another, nor controlled-save the “who pays”, because, frankly, no “right” can obligate someone else to pay for something another claims as a “right”. The state already has too much involvement in everyone’s lives. I see little value in inserting it into even more of our lives.Report

Thank you, @damon

But I think much of my point here is that women have a lot of tradition inserting itself into their rights, and from what I can see, it’s only the actions of states that give them access to those rights. Men, for instance, were given the right to vote simply due to being men. Women needed the state to take action to grant them this right. So I think you can see why I have some qualms about your stance; I cannot take for granted the things you can.Report

@zic,

Indeed, you are correct, but my point was rather narrow. Western society has made a lot of progress in terms of various oppressions, and that’s a good thing. But, let’s also be mindful that state action, by it’s very nature, is oppressive and violent. That’s not a servant I wish to engage very often. The blow back can be a bitch. Contrast that to many others who view the use of the state to achieve their desires as a first choice.Report

Not everybody agrees with the proposition that government or state action is by its nature oppressive and violence. What I think is that a state has a great capacity for good and evil acts. The greater the capacity of a state to act than the more good or evil it can be. A government that is capable of providing universal healthcare is also one that can really intrude into a person’s life. I think that many liberals and libertarians could agree with this framing. Where we disagree is that liberals do not believe that decreasing the government capacity to do good will necessarily decrease its capacity to do evil since many acts of state oppression and violence come from its police and judicial powers, which can exist in a limited government framework.Report

Lee,

I agree that gummint can do good as well as bad. I tend to think that the types of disputes we get into here at the OT revolve around a pretty complex calculus which none of us ever make explicit, and it’s this: liberals tend to think that the benefits of gummint outweight the costs and libertarians tend to think the opposite. At one extreme end of libertarianism you have the view that gummint is not and cannot be justified (Michael Huemer, for example) coupled with – or striding alongside of, anyway – the idea that gummint can be defined as a monopoly on the use of force. I’m not sure what the liberal extreme would be – maybe something to the effect that any gummint policy that passes formal muster is legitimate? (I know Jaybird will want to chime in with references to Stalin, of course.)

But back to the calculus part… I think an objective appraisal of gummint would conclude that it does some good stuff and some bad stuff. My liberalism is based on the idea that on balance, government accords more good than bad. Damon’s libertarianism is based on the idea that gummint does more bad than good.

I throw this out there since I think resolving these types of view in any sort of non-ideological way is pertnear impossible. I just don’t think any of us has the mental/intellectual/emotional/computative capacity to determine an answer to this issue in any definitive way.

So … we resort to cheats. We extrapolate from one policy area to another. We generalize. We simplify. Either empirically or emotionally or partisanly. Whatever!

For my part, I’m 100% on board with zic’s claim that without gummint intervention into some serious issues, women wouldn’t enjoy the options and opportunities that they currently do. In fact, as some folks already know, I think conservatism to a great extent is motivated by a desire to curtail the types of equalities zic consistently argues for. Libertarians who object do so for other reasons. At the end of the day, tho, when we try to make a judgment about the role gummint plays in all this, we’re just arguing for our own preconceptions. Granted, some people come into an issue with fewer priors and can make a legitimate claim to “dispassionate judgment”. But as we’ve been learning, quite often dispassionate judgment is just the expression of privilege, or High Intellectualism, or somesuch. In other words, a defeatable framework.

For my part, tho, I’m still really down on all the a priori stuff. There’s carts, and there’s horses, and the a priori cart has no business leading anything.Report

@stillwater, Stalin is not a good choice for the liberal extreme because he was a Communist and not a liberal and your getting into debates on what is the difference between a modern liberal and the various types of socialism. The liberal extreme would probably somebody from the French paternalist school of government who simply accepts the idea that government should act as a very strong guiding force in society.

I agree with you and zic that government intervention is necessary to carry out societal reforms in many instances. America would be a more traditional or conservative place with fewer opportunities for women or people of color without government intervention.Report

@stillwater

Given the number of humans “gov’t” has killed in the 20th century, I’m pretty sure, on balance, gov’t has caused more harm than good to humanity. What are we up to now, 100 million?Report

Is Stalin a Communist again? Golly, how times change. I remember when it was risible to say that he was one.Report

@damon

Rummel now says a quarter billion.Report

What party did people did people used to think he was General Secretary of?Report

@mike-schilling

Well, while the Chinese communist party has the word communist in its name, the Chinese government has stopped issuing quotas (or at least increasing them) and allows its people to keep their productive surplus instead of collectivising it. That seems distinctively un-communist to me. Also, wasn’t it the case that in communism the state was supposed to wither away? But that didn’t happen in Stalinist Russia.Report

You have to distinguish Communist from communist.Report

Well a right to a fair trail can lead to all of us paying for public defenders for the accused.Report

And a right to contract enforcement and property protection obligates the rest of us to pay for courts and judges and police.Report

There’s an important distinction between “we’re all required to contribute to a common fund, which will pay for X for those who can’t afford them” and “you, by virtue of your relationship with the person who can’t afford X, are obligated to make X available to them.”

It’s the difference between public funding for housing assistance and requiring you to provide or pay for a room for that person.

Some libertarians pretend there is no such distinction. They’re wrong. Liberals who make the same pretense are no less wrong, and they’ve also played into the libertarians’ hands by agreeing that we can’t make such distinctions.Report

The ironic thing with your argument here is that women pay for their HL insurance; it’s part of their employee compensation, and it’s HL doing the rent seeking, putting the cost on tax payers.Report

women pay for their HL insurance; it’s part of their employee compensation

Really, do they pay for their wages, too?

And the claim that “it’s part of their compensation” treats that as an “of course,” rather than what it really is, which is an attempt to make it true via law. Insurance as part of compensation is not inherent, nor then can any particular part of it be inherent. What we have, in our politics and in our law (including the HL case) is a negotiation about whether contraceptive care is in fact to be a part of compensation or not. To simply say that it “is” part of their compensation is to pretend that this isn’t a political/legal issue that is being negotiated.Report

@james-hanley

The former being unworkable for the health insurance mandate, of course. Any employer could develop a genuine religious objection to covering anything expensive like cancer or heart attacks (“But we cover 100% of your yearly flu shot!”). It’s a path to single payer, I suppose.Report

@james-hanley

I do understand your point, but would point to the way schools were funded by property taxes, on the theory that homeowners tended to be parents of school aged children.

But lets look at this-

“you, by virtue of your relationship with the person who can’t afford X, are obligated to make X available to them.”

What is the argument against this? Why is this universally illegitimate?

Why can’t we, in LiberalWorld, say that employers are mandated to provide transportation (public, of course) for their workers?Report

Schilling,

I am on record as saying that single-payer was both more sensible and more clearly constitutional than ACA. And I am not bothered by the prospect of claims you lay out, both because it’s really reaching to assume there’d be lots of those types of claims and because I am willing to defend conscience rights very broadly.

LWA,

What’s the point of debating that. You already actually know what my position will be, I already actually know what your position will be. There’s no prospect of either of us saying anything new and informative, and no prospect of either of us winning over the other.Report

I still say “Everybody-on-the-exchanges” is far more likely (or less unlikely) than single-payer.

(Well, between the exchanges and Medicare/Medicaid, some combination of both.)Report

it’s really reaching to assume there’d be lots of those types of claims

I think many companies would get over their embarrassment at saying something dumb if it resulted in shedding themselves of most of their health care costs.Report

Mike,

Sure, Mike. Because the HL ruling clearly applied to publicly-traded corporations, and because there’s such a vast number of people employed by closely-held corporations that want to offer health insurance but don’t want to pay for it.Report

“Everybody-on-the-exchanges” is far more likely (or less unlikely) than single-payer.

Agreed.Report

“Everybody-on-the-exchanges” is far more likely (or less unlikely) than single-payer.

On Tuesdays — I only believe in conspiracy theories on alternate Tuesdays — I sometimes say that this was CJ Roberts’ plan all along. Keep the for-profit insurance companies in the loop, generate lots of revenue for Big Pharma and Big Hospitals, and eventually get corporations out of the employee health insurance business with its high inflation rate and into a scheme where their payments are capped as a matter of tax law.Report

Because the HL ruling clearly applied to publicly-traded corporations

Not yet. But the same logic that gave all corporations freedom of speech (excuse me: restored the freedom of speech of investors (who if their direct investment was in a mutual fund, might not even know that they’re investors), where freedom of speech means allowing corporate management to attempt to influence elections using their money. Are we happy now?) could give them freedom of religion too. After all, if Exxon stockholders don’t agree that it should profess a religion that combines the medical views of Christian Science, Jehovah’s Witnessism, and Scientology (as applied to psychiatric care), they can always replace the Board of Directors.Report

Mike,

Absolutely. If we can conceive it, the odds of it happening must be unacceptably high.Report

@james-hanley

“It’s the difference between public funding for housing assistance and requiring you to provide or pay for a room for that person.

Some libertarians pretend there is no such distinction. They’re wrong.”

Count me in that category. We’ll have to agree to disagree on it being wrong. Force is force, in whatever it’s manifestation.Report

@james-hanley

What’s the point of debating that [‘“you, by virtue of your relationship with the person who can’t afford X, are obligated to make X available to them.”

What is the argument against this? Why is this universally illegitimate?’]? You already actually know what my position will be, I already actually know what your position will be. There’s no prospect of either of us saying anything new and informative, and no prospect of either of us winning over the other.

It’s not clear LWA knows your exact yea-nay position on the question (I don’t – Always illegitimate? Sometimes legitimate? When?), but it’s certainly clear he doesn’t know your reasons for it, which is actually what he asked after. The point of his question was not necessarily to inaugurate a debate, but to ask about the reasons for your position. And to the extent there were to be a debate, the point of that would not necessarily be for one of you to convince the other, but to adumbrate said reasons for the benefit of a) LWA’s understanding of your reasons, and b) the readership’s understanding of the larger issue overall.

I’m curious about the same question that LWA asked, and I profess I don’t know the answer to it.Report

I am not James, but I can take a stab at a response that is roughly in line with a libertarian-ish thinking.

The moral libertarian argument would point out that all government mandates rely ultimately on the coercive use of force and the threat of imprisonment, which means that it is unjust to initiate force against people who are not hurting anybody else, even if you believe that their inaction will lead to harm. In other words, using force against people simply because they do not wish to be helpful in the way that you wish them to be helpful is unjust.

As I am neither an anarchist nor a minarchist, the moral argument does not clarify much for me; it only raises further questions about the legitimate use of government force.

Instead, I will rely on the economic libertarian response and point out that when you enforce a particular arrangement, one based on providing a specific set of goods and services, you are making both parties worse off than you could if you allowed them to freely exchange in the manner that they wish. You might feel that a mandate is necessary, because one party holds a lot more power than the other party, but if that is the case then you ought to address that issue directly.

In short, if you want to improve people’s well-being, stop trying to decide what they need in advance and help them get to a place where they can bargain for themselves.

Of course, you, as progressives, can say whatever you want to say. You can design the perfect progressive utopia and go about trying to implement it. You will, however, be faced with the reality that you all in LiberalWorld have to deal with all those people in SocialCon world and LibertarianWorld and IHaveNoIdeologyButI’mStillNotInterestedWorld.Report

@j-r

Thanks. I’m intersted in James’ answer in particular, but I appreciate yours as well.

So it seems to me that if your answer really is the consequentialist one and not the deontological one, then then you’re not saying it would be illegitimate; you’re just expressing an opinion about the preferable policy. You might convince LWA not to mandae employer provision of transportation because of the effects, but he might surprise you and convince you of the good effects of mandating employer provision of something else. And even if you convinced him that it would be a bad idea in every individual instance, it still wouldn’t have been established that it’s categorically illegitimate and would be illegitimate even if you both were suddenly to flip on one proposal and start to think it would be a good idea to mandate it.

So I think the issue comes down to whether you sand behind some version or other of the moral argument against it. James says we don’t mandate that X must provided Y with smething by virtue of their relationship, but of course we govern people’s conduct wrt to certain others by virtue of their particular relaionship all the time. I don’t *think* James is arguing against that. So the argument would have to be against mandating provision of some good or other by virtue of a particular relationship. (Kepp in mind, the issue is not mandating that person A walking down the street give $5 bucks to person B walking down the street the other way.) So I’m curious what the particular (moral/civic, not so much consequentialist) argument against mandating provision of things within a particular kind relationship (in particular, employer-employee) is if(!) we agree that mandating other restraints on conduct by parties that kind of relationship.Report

Zic, I am sure you expected some heat from this post so I will not pull my punches here. Please see that as a sign of respect.

The reason why Hobby Lobby happened is because a lot of people believe employers should also have to pay for abortions. It’s a line in the sand. Now, if someone on the Left wants to make a clear statement that abortion and contraception are not equal in the ‘family planning toolkit’ then maybe it would alleviate some of those fears, but I don’t see anyone doing that.

92% of Down Syndrome fetuses are aborted. This number is up dramatically since genetic testing has become more reliable. There is nothing else to call that except the goverment-sanctioned culling of our population. I don’t see anything in this post which leads me to believe that this trend will stop and THAT is what many of us oppose.Report

I would argue that taking on the challenge of parenting a child with down syndrome is a huge responsibility; and a woman has the right to decide if she’s up to that challenge.

I also don’t have much issue with the notion that health care should pay for abortions; particularly if universal access to contraception is available as part of health care. Short of sterilization, not form of birth control is 100%; there are always the potential of unforeseen health problems, not to mention decisions about parenting a child with severe abnormalities.

To me, it’s the morality of responsibly procreating that matters; procreation by chance is immoral.Report

Zic,

“I would argue that taking on the challenge of parenting a child with down syndrome is a huge responsibility; and a woman has the right to decide if she’s up to that challenge.”

She doesn’t have to be up to the challenge…you know that right? She isn’t legally obligated to care for the child. There’s a gulf between ‘it’s too hard for me to care for you’ and ‘you would be better off not being born’. Somewhere in-between is the decision to put the child up for adoption.Report

To me, it’s the morality of responsibly procreating that matters; procreation by chance is immoral.

Hoo boy, does that get into a lot of eugenics issues.Report

My wife and I potentially procreate by chance whenever we have sex, since abortion is not something we would consider and contraception is not 100% reliable. If she had become pregnant before we were ready, would declining to abort have been immoral?Report

procreation by chance is immoral.

Our third child was wholly a product of chance, not planned, and initially not desired.

The implications of your statement are… troubling.Report

Re: “procreation by chance is immoral”

Allow me to suggest that @zic’s meaning was that the enforcement of any procreation by chance that any (woman?) would like to have avoided (i.e. allowed to determine by affirmative choice if possible), even if enforced “merely” by the society’s failure to alleviate economic inequality (by nearly any means necessary so long as not not baldly and grossly immoral for some other reason*) that would have allowed many women a chance to replace chance with choice, is immoral. Obviously zic can inform me that that was not her meaning at all, but my sense from the OP is that it was.

* Granted, a potentially rather huge caveat, depending on the values inserted for “immoral” there.Report

@will-truman

My wife and I potentially procreate by chance whenever we have sex, since abortion is not something we would consider and contraception is not 100% reliable. If she had become pregnant before we were ready, would declining to abort have been immoral?

Irrespective of whether it was @zic ‘s intention to suggest that it might have been, I’m going to suggest that, abstractly speaking, it could have been. In your case, in actuality, it certainly would not have been. So I’m talking about a hypothetical you and Clancy that aren’t really you and Clancy here. But I take the meaning of your question to be about the abstract case, not specifically what it would have been moral for actual-you-and-Clancy to do. So if you two had been drastically less ready than you had been to the point that to have had the child and to raise it (let’s also say that this hypothetical couple were determined not to give the child up for adoption and would not have done so despite any entreaties to do so, as is the case among many prospective unfit parents each year) would have been to bring a person into the world to whom great harm was going to be done starting at birth and running through most of childhood, then, yes, I think in that case given those two possible eventualities, that couple actually was morally obligated to abort. Or at least, on the whole it would have created a morally better situation for them to have aborted the pregnancy.

To put it more simply, yes, I believe that each year a significant number of childbirths happen that should not have happened; that morally, given the realistic reality that the children would not have been given up for adoption and that this means that their fate was to be raised by radically unfit parents who would do harm to the real people that the zygotes never were and could have been prevented from becoming, many of those pregnancies should have been aborted. The only real reason that they shouldn’t have is because in many of those cases the resources for the abortion was not available. That’s an argument for either public or charitable provision of family planning services for the poor and marginalized and otherwise unfit up to and including abortion service. (I feel the need to add here that no one should ever be coerced into, or out of, electing to abort a pregnancy.) Further, the lack of resources available to have an abortion in my mind is underscores the extent to which the resources to responsibly raise a child in this situation were absent in the first place. (Not that simple lack of resources implies that a pregnancy should be aborted; that’s something that can be built up over time. A deeper form of unfitness such that abuse is likely is necessary IMO.)Report

@michael-drew I pretty strongly disagree, though I do understand where you’re coming from. I am hard-pressed to come up with a circumstance where declining to abort is the immoral (as opposed to, in some cases, morally acceptable or neutral) thing to do. But if I didn’t have those priors, I might well look at abortion the same way I look at sexual behavior that can produce an unwanted and/or unprepared-for child which I see as, if not immoral, then in a neighboring ZIP code.Report

I’m sure you’ve heard the rare and safe slogan from pro-choicers on the subject of abortion. You may also have heard them talk about how the best way to make abortion rare is to prevent pregnancy in the first place, and most realistic way to do that is through access to contraception. That said, access to abortion is as important to reproductive freedom as is access to contraception. So, while they are different, and while pretty much everyone who’s pro-choice recognizes this, if you’re looking for people to separate them by saying “people should have access to one but not the other,” where access to medical procedures in our system is largely determined by insurance, and insurance is generally provided by employers, then you’re probably not going to get that.

So, it seems to me that pro-choicers are the ones who recognize the difference, but who understand that with respect to women’s health and independence, they are both necessary. It’s the other side that doesn’t seem to recognize either of these propositions, as evidenced by the fact that you say that in order to prevent abortion they draw the line before contraception.Report

Chris – the line gets drawn because, as you and Zic both point out, most pro-choicers see no difference between contraception and abortion. That is why abortion is the preferred method of contraception for many in blue states and that is why the HL case mattered.Report

That is why abortion is the preferred method of contraception for many in blue states. . .

You’ve got to be kidding me, @mike-dwyer. If you’re going to suggest this, you’re going to have to substantiate it. But I would encourage you to revisit a notion here that women easily seek out abortions as if it were a lark, too; instead of recognizing that having an abortion is one of the most difficult decisions a woman will ever make.Report

Zic,

‘Preferred’ may be a bit of hyperbole, however ‘favored much more than in red states’ seems accurate:

https://ordinary-times.com/blog/2012/02/22/the-abortion-post-i-didnt-plan-to-write

It may be a difficult decision but the facts show that it is a decision many women make more than once.Report

Mike,

Most women seeking abortions were on the pill, weren’t they?

Given that abusive men seem to feel impregnating women who do not want to be pregnant….

How many of those abortions are because the women PREFER them,a nd not because someone stole their birth control pills? (or, god forbid, replaced them with fertility pills).Report

I just pointed out one way in which pro-choicers see a difference. We see a difference. We just think they’re both necessary. Again, it’s the pro-lifers who see no difference, or at least act as though there’s no difference by drawing a line before contraception. It’s not like pro-choicers are trying to make laws that affect both.Report

Put differently: pro-choicers do not see contraception as a gateway to abortion. We see them as completely separate things. Pro-lifers, on the other hand, fail to make a distinction, at least in practice.

The problem is on ya’ll.Report

Mike,

I notice your 2012 analysis left out any attempt to adjust for availability of abortions.

Surely red states don’t have as many abortions as blue states, because red states have been doing everything they can to insure NO ONE can have an abortion. Texas is one those leading the charge.

I understand the official abortion rate in some South American countries are very, very low. The unofficial rate is, of course, much higher.Report

Morat20,

Per this map…

http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2013/01/22/the-geography-of-abortion-access.html

Access doesn’t really seem to be a huge problem unless you living in the middle of the country and that seems fairly attributable to the sheer distance people live from cities. I feel like the access thing is a bit of a red herring. The reason for the difference in abortion numbers is simply a cultural thing.Report

Chris,

You say that you don’t see contraception as a gateway to abortion, and maybe you don’t, but the OP and Zic’s subsequent comments seem to strongly indicate she sees the two items as linked. When she says that access is a universal right, how could anyone argue that a healthcare plan shouldn’t include both? That’s where the problem occurs. It goes back to my old complaint which is that too many liberals see rights where they don’t exist.Report

The state-to-state disparities predate the somewhat recent spate of anti-abortion legislation. The best statistics I found were from either 2004 o 2008. I suspect that if I went back to 1980 they would nonetheless tell a similar story.

A quick perusal: In 1980 there were 97,000 abortions by Texas woman, and 178,000 abortions by New York women, when the population difference between the two was pretty small (14m to 17m). Around 4,000 Utah abortions, compared to a little under 4000 in Delaware, with Utah have over twice the population. 8,000 in Arkansas versus 6,000 in Rhode Island with the former having twice the number of people.

There are outliers, I’m sure. And I think there is more to it than culture. Not just regulations, but rural vs urban (though I did choose Utah precisely because it’s not particularly urban) and cost-of-living (and thus the cost of having children). Even so, I have yet to see anything that suggests that culture isn’t a significant component.

(Note: These numbers are by state-of-residence and not the state where the procedure was performed.)Report

@mike-dwyer

There are some good maps for state-by-state comparisons here:

https://www.guttmacher.org/statecenter/unintended-pregnancy/

That’s unintended pregnancies, there’s a link on the left for abortions.

I don’t think simply looking abortions alone is enough, though. Unintended pregnancies that result in live births matter, which is why I linked the map I did. I would be most comfortable seeing a very low unintended pregnancy rate, indicative of responsible contraceptive use. The third piece of information needed, which these maps don’t provide, is how poverty impacts these numbers; particularly in states like Delaware, New York, and Texas.Report

A color-coded map on abortions as a percentage of pregnancies is available here. Numbers from 2008, if I recall.Report

Mike,

I’d be far more impressed if you were quite so militant against American Eugenics policies.

We still have Eugenics laws on the books, and they’re still (often) enforced.

To me, it is a FAR worse restriction on liberty to say “You may not bear children” (or even forcible sterilization), than to simply abort a child upfront.Report

Great piece, Zic. While I have my doubts as to whether you can call access contraception a universal human right, I don’t think there can be any argument that women’s ability to control their fertility and determine when and how many children to have (to the greatest extent possible) is central to women’s rights and personal economic freedom. To me, it’s a social choice we make to empower women, to improve their health and the health of their children, and to provide them with full equality.

I further agree that the individual woman’s conscience supersedes whatever conscious a for-profit corporate person might have. Hobby Lobby’s expansion of corporate personhood to include religious consciousness is what disturbs me most about the decision.Report

Why can’t you call access to contraception a universal human right?

This is an argument I’ve gotten into before, not necessarily over contraception, but over expanding the concept of what is and what is not a human right. Conservatives (including people here) have told me that one of their problems with the left and liberalism is that the left and liberals are constantly expanding the concept of what is and what is a human right like public transport and internet access.

I honestly don’t see a problem with this. I don’t see why the concepts of human rights need to be locked and frozen in the time of the ideas of Locke and the Enlightenment. We live in a highly connected and globalized world and wealth building and livelihoods are dependent on such things.Report

Saul–I suppose it might be subsumed under a right to privacy, but I don’t see it as a right in and of itself. Ditto for access to health care. These are political and economic choices that civilized societies make; there’s nothing inherent about them.

Would I prefer to live in a society where health care is available to all and where access to birth control was part of that health care. Yes, and thus I vote accordingly and do what I can to work toward that goal.

Moreover, I’m not sure that making everything part of the “rights” debate really helps the cause because rights are considered inviolable, but they invariably conflict with other sets of rights. Which rights take precedence? It’s a political choice.Report

Seems to me that it sort of works like this (and Zic makes a good argument for it, though I think she’s trying to make an even broader argument): To the extent that health care is a universal right, then so too should contraception because contraception is critically a form of health care.

Whether one accepts the second part (that contraception is a human right) depends highly on what they think of the first (that health care is a human right).

There may be an argument that contraception is a human right apart from whether we consider health care one, but I’m not particularly sold on that.Report

@saul-degraw

I’d think most libertarians wouldn’t consider expanding public transport and internet access as “rights”. It generally goes against their entire would outlook.Report

Will and Michelle,

Right to Autonomy over one’s own body is the proper originating right, not privacy, nor health care.Report

Regarding the charts:

The first chart shows that maternal mortality in the US fell very sharply between 1920 and 1950,before the advent of the birth control pill. Off the top of my head, I would guess that medical advances such as the discovery of penicillin in 1928 had a lot to do with this (the slope of the decline becomes much sharper shortly after 1928), although clearly there was also something in the start of the 1920s that sparked the decline. Regardless, it’s very clear that the birth control pill didn’t have anything to do with with the major decline, since maternal mortality was already very low (compared to previous decades) by 1960.

For the second chart, I have to question the direction of your cause-effect theory. The inverse correlation between median income (or GDP per capita – which isn’t as good a measure as median income but is far more widely available) and fertility is a worldwide trend. It holds true even for countries and regions where women have very little power. It’s a very marked trend in the Middle East and North Africa. The developing region where the trend is least evident is sub-Saharan Africa, which is also the region that has seen the least income growth (a long periods of income decline) over the last 60 years. (I’m using data from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators.)

It is a very widely recognized phenomenon among people who study development, and the causality is widely considered to work in the opposite direction – as people become wealthier, and as infant mortality declines, families have fewer children. There’s very likely a reinforcing effect where fewer children in turn reduces a family’s costs and makes them better off, but the starting point of the spiral is rising incomes. When people are better off, and face less risk of their children dying at an early age, they have fewer children.

North America in the 1960s is a clear outlier, in that fertility rates fell much faster than would be expected from the increases in income, and that, presumably, is due to the advent of the birth control pill.

My preferred outcome, given what we have for a political system, legal precedent, and statute would be for employees working for corporate objectors to be covered by the government and or insurance companies in a way that seems seamless to the employee; while corporate objectors pay for their objection with a tax penalty exactly as real, non-corporation people pay a tax penalty when they decline to purchase health insurance, thus offsetting the rent-seeking objectors are placing on everyone else.

I would agree with that as the best way of dealing with contraception under the Affordable Care Act.Report

There’s very likely a reinforcing effect where fewer children in turn reduces a family’s costs and makes them better off, but the starting point of the spiral is rising incomes. When people are better off, and face less risk of their children dying at an early age, they have fewer children.

I don’t think it’s so easy to separate out; but rising income generally goes hand in hand with contraception — first, the ability to afford it, and second, the increased income the woman brings into her family because she’s able to work instead of churn out baby after baby; based on the UN report. I don’t suggest that this is simple; but there’s no doubt that access to contraception correlates with increased family wealth and rising living standards. Here in the US, this is reflected by the fact that it’s women in poverty most likely to have unplanned children.Report

The broad theory is that both are true: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2013.00557.x/abstract

According to conventional demographic theory, high fertility in the early stages of the demographic transition is the consequence of high desired family size. Couples want many children to assist with family enterprises such as farming and for security in old age. In addition, high child mortality leads parents to have additional children to protect against loss or to replace losses. Fertility decline occurs once rising levels of urbanization and education, changes in the economy, and declining mortality lead parents to desire

a smaller number of births. To implement these desires, parents rely on contraception or abortion, and family planning programs in many countries accelerate their adoption (Notestein 1945; Easterlin 1975, 1978; Lee and Bulatao 1983).

This theory is widely accepted as a broad outline of the forces that shape fertility transitions and is consistent with much empirical evidence (Bryant 2007). As countries develop, fertility generally falls and there is a strong inverse correlation between development indicators and fertility in contemporary societies (with Africa characterized by relatively low levels of social and economic development and, accordingly, high fertility). The theory is not without its critics, however, who claim that fertility change can be brought

about by ideational change and the diffusion of ideas.

In short – as people become economically better-off and as child mortality declines, they want to have less children. At this point, increased access to contraceptives is useful and desirable.

Charts later on in the same article show women’s “ideal family size” (the number of children they’d like to have) based on surveys of women in different regions. In sub-Saharan Africa, numbers are very high, with country averages ranging from 4 to 9; this somewhat accords with the actual average fertility rate in sub-Saharan Africa, which is 5. Ideal family size in Latin America and east Asia is substantially lower – and so are fertility rates ( in the 2-3 range).

So at very low levels of income (and generally in more agricultural economies), people tend to want – and may economically benefit from the labour of – more children; in those situations, increased use of contraception wouldn’t by itself have a substantial positive impact on economic well-being.

As people become economically better-off, both their demand for and their access to contraceptives increases.Report

Use of contraception doesn’t particularly correlate to availability of contraception. For example, the total fertility rate in the US spiked during the postwar years but by the 1960’s was returning to the levels it had been. There are always methods available. The issue seems to be one of culture.Report

@zic @katherinemw

For what its worth, fertility rates in Singapore have plunged have plunged in Singapore accompanied by a rise in education levels for women without extensive use of birth control pills. I don’t have data on birth control pill usage (though other forms of birth control may be used instead) in Singapore. While IUDs and implanon are the dominant forms of birth control used now, implanon is rather recent. And at least, if celebrity blogger Xiaxue is to be believed, usage rates of birth control pills is very low. This makes it seem more probable that the drop in birth rates over here (it dropped below replacement in the mid 70s) was not brought about by the availability of the pill specifically (though of course it was probably brought about by education and the availability of other forms of contraception including abortion)

That is to say, if high birth rates can be curtailed without the pill in one country, it is rather dubious to say that availability of birth-control pills is required for women to exercise control over their bodies. or for that matter to attribute a similar decline in birth rates to the pill in your country (at least in the strong way that you are doing). As Katherine has mentioned above, it is not the pill, specifically, but contraception writ large that provides women with control over their bodies.

Incidentally ,while the hobby lobby case was silly in that the greens had a wrong idea of how the particular contraceptive devices and pills in question worked (i.e. they were not abortificients) they did not refuse to cover all contraceptive pills and devices, only some types of contraception. Most women would still have had their contraception covered.Report

Murali,

You’ve apparently not heard of the “popping pinholes in the condom” approach to family planning. The right to autonomy over one’s own body is infringed upon daily — sometimes by guys substituting other pills for someone’s birth control pills.Report

Which is relevant to my discussion how? As a matter of fact, (at least to the best of my second hand knowledge from my family members, three of whom are doctors and 1 who is a medical student, prescription of contraceptive pills is very rare. It is certainly rarely prescribed to teenagers. Yet, there has been a steady drop in birth rates even through extensive pressure by the government to increase fertility. This demonstrates a tremendous ability by women to successfully control their own reproduction regardless of low rates of pill use.Report

Katherine,

Most probable decrease in maternal mortality is due to more widespread adoption of handwashing and sterilization, at least in part due to the formation of our modern “Medical Schooling.”

I’m not certain that all the maternal mortality deaths are being reported properly. One takes poisons early on if one wants to kill the unborn, after all. One might not expect “died of poison” to be counted as “maternal mortality” in all cases.Report

I’ll take @leeesq’s challenge. I will first say, however, nice work on the piece and that I object to almost none of the substantive parts of the piece in regards to the importance of contraception or to the desirability of working towards access to contraception for all women.

That being said, I do want to comment on this statement:

The reason that reproductive healthcare rights are not accepted as inalienable is because they are not inalienable. And that is not me expressing an opinion or even stating a philosophy. Rather, that is me simply alluding to the definition of inalienable: “incapable of being alienated, surrendered, or transferred.” When we speak of inalienable rights, we speak of a metaphysical condition and not of a desired state of affairs. The right to speak your mind is inalienable, not because it is wrong to take it away, but because it cannot be taken away. A person’s mind is his or her own and someone may infringe upon it by use of coercion or force, but it remains the case that my voice is my voice as long as I live and even after I die it is no one else’s.

To speak of access to any good or service, be it reproductive health care, any other sort of health care, education, etc., as a universal right is a statement of aspiration. We wish it to be so, which is fine. It is just important to remember that wishing something to be so is not the same as it being so. Access to something can never be an inalienable right, because it necessitates that some other person take positive action to provide it for you. There is a real an meaningful difference between saying, “leave me in peace to do as my body what I wish” and saying, “you must do your part to provide me with this particular good.”

None of that is to say that i do not believe that we as a society ought not impose certain types of positive action on each other. We pay taxes to provide for public goods and I fully support maintaining access to a modicum of reproductive health care services as one of those public goods. The relevant issue here is that this is much more an entitlement than it is a right. And that is important to how we go about building consensus on how best to provide that entitlement.Report

The relevant issue here is that this is much more an entitlement than it is a right.

You are not entitled to someone else’s uterus.Report

OK, I thought that I was making my point fairly clear, but perhaps not. Here it is:

The ability of an individual to do what she wishes with her body in the form of seeking to procure reproductive health services is an inalienable right, by definition.

The desire that an individual be provided certain goods and services by another person or group of people, while in many cases desirable, is not an inalienable right, by definition.

As soon as you place a responsibility on a third party to provide or help provide some good or service, you are necessarily giving that third party a voice in the transaction, again, this is by definition.

You may wish that person not to have a voice, but they do. And they have that voice, in part, because you brought them into it. Therefore, if you don’t want third parties having a voice in how women use their uterus(uteri?), your best bet is to get third parties out of the picture to as much a degree as possible. And the best way to do that is to move towards a model of health care provision that lets individuals procure goods and services with their own dollars and not through some third party who is legally obliged to comply.Report

Good thing he wasn’t talking about controlling someone else’s uterus, then, eh?Report

Is anyone claiming to be entitled to someone else’s uterus?

Because when I flop this around to, oh, weed or something, it becomes an argument about whether I should have to provide weed to you and whether you have the right to smoke weed.

Arguing “you are not entitled to someone else’s lungs” is an awesome argument against the prohibitionists who say “you do not have the right to smoke weed and we’ll throw you in the hoosegow if we catch you doing it” but it’s less of a compelling argument against the person who says “Buy your own weed.”

All that to say, it’s totally cool to argue against the Hobby Lobby ruling and those who agree with it. I just don’t think it’s cool to argue against the Hobby Lobby ruling as if it were Prohibitionist. It’s not.Report

This sort of ignores the elephant in the room: an ongoing effort to not only eliminate the legal right to abortion, but to continue to allow discrimination against women when it comes to basic and essential health-care services.

You’re free to focus on HL as not going there, but you would first need to go look at the history of the foundation which actually put fourth the case on behalf of the Greens, where the groups funding comes from, and the history of cases it’s pursued. (Hint: Beckett Fund.)

I am not writing to HL as the whole problem, but as a symptom of a larger problem of denying women the basic human right of controlling their own reproduction, and thus, their freedom and destiny. IReport

I’m with Jaybird on this. And it’s an effective argument, because the idea of mandatory government provision of weed is making me laugh.

It’s entirely legitimate to say “[x] set of services are essential, and government has a responsibility to ensure people have access to them”, where set [x] can include contraceptives, health care, education, clean water, sewage treatment, housing, food, whatever. And I personally don’t have an objection to referring to these things as “rights”; libertarians typically do object to such terminology.

But there’s an important and unavoidable distinction between not providing things, and legally barring people from having things. The issue of contraception (I won’t get into the abortion debate here, because the argument is unproductive – pro-life and pro-choice people disagree about how many people possessing rights are involved in the action: one (pro-choice) or two (pro-life)) falls into the former category.

The HL case is something else entirely, concerning whether religious business-owners have an unalienable right to tax breaks, even if they don’t take the actions that those tax breaks are designed to reward.Report

I hate to pile on here but I do agree. I’m a staunch supporter or choice in the area of reproduction but saying that contraceptive and reproductive choice is a right is problematic.

I would say that you have a right not to have others interfering in your choice whether or not to conceive and whether or not to have an abortion.

I would say you have a right not to have others interfer in your ability to purchase contraception.

Where I struggle is the idea that one has a right to be provided with contraception or abortion services at no cost. That them implies that someone (or everyone?) has an affirmative natural obligation to provide these things. That’s where I struggle with positive rights.

Now if we say that it is excellent policy to provide free contraception and abortion choice to everyone then I’m 100% on board. When we start calling it a human right is where I think the wheels come off.Report

I say we do the only sensible thing and stop talking about rights altogether.Report

@chris

That would make my day.Report

Jaybird, Katherine, North,